A study on worms led by researchers from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in the US has uncovered a previously unknown adaptation to aging that actively remodels one of the largest and most complex structures in our cells.

Not only does the finding help clarify the cellular mechanics of aging, but it may also hint at a possible drug target for age-related chronic diseases.

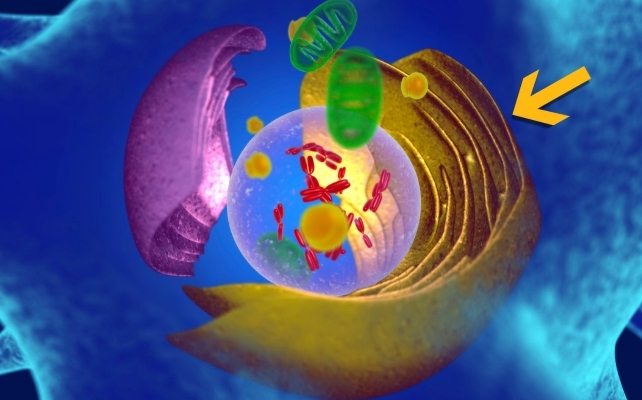

As humans and other animals grow old, our cells modify their endoplasmic reticulum (ER) – an extensive transport system that plays a critical role in various biochemical processes such as protein folding.

Cells carry out this modification using ER-phagy, a mechanism only discovered in recent years.

ER-phagy is a type of autophagy, a natural process in which digestive enzymes break down and recycle a cell’s damaged or unnecessary components. In ER-phagy, specific subdomains of the ER, such as damaged or excess portions that could threaten cellular health, are selectively targeted to be broken down.

The new study, however, reveals ER-phagy also plays a role in healthy aging – and possibly in lifespan extension, too.

“Where many prior studies have documented how the levels of different cellular machineries change with age, we are focusing instead on how aging affects the way that cells house and organize these machineries within their complex inner architectures,” says Kris Burkewitz, a biologist at Vanderbilt University.

Eukaryotic cells’ ability to function depends on the efficiency of individual organelles, but aside from merely being in the cell, their arrangement and distribution matter, too.

It’s sort of like a factory, Burkewitz says: Simply possessing all the right machinery won’t make your factory productive unless that machinery is set up in the correct position and sequence.

“When space is limited or production demands change, the factory has to reorganize its layout to make the right products,” Burkewitz says. “If organization breaks down, production becomes very inefficient.”

That’s where the ER comes in. It consists of multiple structural subunits, each associated with particular functions. The rough ER synthesizes, folds, sorts, and transports proteins, for example, while the smooth ER synthesizes and stores lipids, among other tasks.

A cell’s ER also acts as a scaffold within the cytoplasm, using its intricate shape to help organize other parts of the cell. It can change shape in certain contexts, although many details remain poorly understood.

In fact, despite its many key roles, there’s a lot we still don’t know about the ER – including how and why its structure changes in aging eukaryotes.

To investigate the ER’s role in aging, the researchers studied living Caenorhabditis elegans nematodes, which are widely used as model organisms. Since they’re transparent and age quickly, they’re especially useful if you want to observe a live animal’s cell as it ages.

Burkewitz and his colleagues used fluorescence and electron microscopy to image the ER dynamics in both young and old nematodes, revealing interesting age-dependent morphological changes.

As the nematodes grew older, the amount of rough ER in their cells plummeted, the study found, while the smooth ER changed only slightly.

More research is needed to confirm the significance, but this might help explain some larger-scale effects of aging, like a dwindling ability to maintain functional proteins or metabolic tweaks that change how we accumulate fat.

The findings suggest ER remodeling is a “proactive and protective response” during aging, the researchers report.

Medical science is helping humans live longer, sometimes well beyond 100. Yet this lengthening of lives doesn’t necessarily include strengthening of bodies, leaving many people to spend their golden years battling frailty and chronic illness.

Related: Scientists Discover a Way to ‘Recharge’ Aging Human Cells

Follow-up research will continue to investigate ER dynamics throughout the aging process, aiming to clarify precisely what’s happening and why – as well as how we might leverage that knowledge to promote healthy longevity.

“Changes in the ER occur relatively early in the aging process,” Burkewitz says. “One of the most exciting implications of this is that it may be one of the triggers for what comes later: dysfunction and disease.”

The study was published in Nature Cell Biology.