Researchers have resolved a 50-year-old scientific mystery by identifying the molecular mechanism that allows tissues to regenerate after severe damage. The discovery could help guide future treatments aimed at reducing the risk of cancer returning.

Many tissues in the body, including the skin and other epithelial layers that line organs, have a remarkable ability to recover after severe damage. Instead of simply breaking down, they can trigger a surge of new cell growth that restores lost tissue.

This process, known as compensatory proliferation, was first identified in the 1970s, when researchers observed that fly larvae could regrow fully functional wings after their epithelial tissue had been heavily damaged by high-dose radiation. Since then, similar regenerative responses have been observed across a wide range of species, including humans, although the underlying molecular mechanisms were not well understood.

When cell death fuels recovery

New research from the Weizmann Institute of Science, published in Nature Communications, sheds light on how this regeneration occurs. The study shows that caspases, enzymes best known for driving cell death, can also help certain cells survive and support tissue repair. By doing so, these cells enable damaged tissue not only to regrow but, in some cases, to become more resistant to future stress.

The researchers also found a potential downside to this process. The same survival mechanism may be exploited by cancer cells, helping tumors return in a more aggressive and treatment-resistant form. Understanding this pathway could therefore inform new strategies to improve wound healing and reduce the risk of cancer relapse.

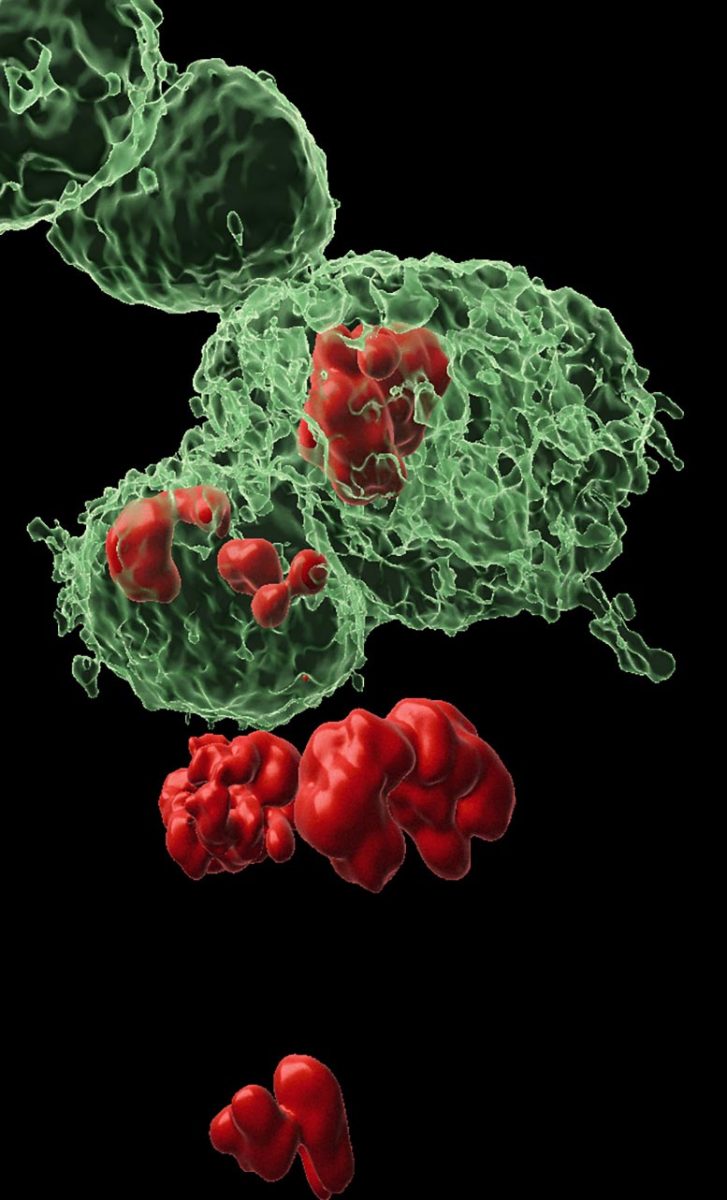

In healthy tissue, the most common form of cell death is apoptosis, a tightly regulated process often described as programmed “suicide.” Apoptosis is triggered when cells age, accumulate damage, or receive signals to shut down. An initiator caspase starts this cascade by activating effector caspases, which then dismantle the cell by breaking down its proteins.

Over the past twenty years, research from many laboratories, including the group led by Prof. Eli Arama in the Molecular Genetics Department at Weizmann, has shown that caspases are involved in much more than cell death alone. They also contribute to essential processes that keep cells and tissues functioning. These findings led Arama, a pioneer in studying nonlethal roles of caspases, to suspect that these enzymes might also drive compensatory proliferation.

Cells that refuse to die

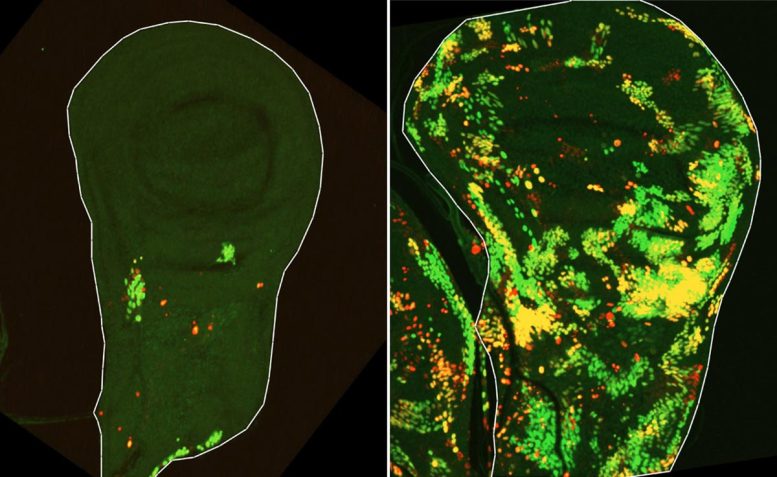

To test this idea, a team led by Dr. Tslil Braun in Arama’s lab repeated the classic experiment that first revealed compensatory proliferation by exposing fruit fly larvae to ionizing radiation. This time, however, they used advanced genetic tools that made it possible to follow tissue regeneration in far greater detail.

“We set out to identify cells that push the self-destruct button but survive anyway,” Braun explains. “To do this, we used a delayed sensor that reported on cells in which the initiator caspase had been activated but that nevertheless survived the irradiation. This is how we discovered a population of cells we named DARE cells. Not only did these cells survive the irradiation – they multiplied, repaired the damaged tissue, and replenished nearly half of it within 48 hours.”

But the researchers also wanted to understand how the rest of the regenerating tissue contributed to this recovery.

“We identified another population of death-resistant cells, but unlike DARE cells, they showed no activation of the initiator caspase. We called them NARE cells,” Braun says. “Although NARE cells ultimately contribute to tissue regeneration, they cannot do it alone: When we removed DARE cells from the system, compensatory proliferation disappeared entirely. We also found that dying cells in the tissue play a role in the burst of regeneration – DARE cells were activated by signals from their dying neighbors.”

Next, the researchers sought to decipher how DARE cells survive radiation doses that trigger apoptosis in neighboring cells.

“We observed that although the initiator caspase is activated in these cells, the cellular death process stops there and does not progress to the next stage,” Arama explains. “We suspected that a protein known as a molecular motor was responsible for this – it can tether the initiator caspase to the cell membrane, preventing it from activating the executioner caspases. Indeed, when we silenced this motor protein, DARE cells proceeded to die and tissue regeneration was impaired. Overactivation of the same motor protein has previously been linked to cancerous tumor growth, which suggests that this might be one of the mechanisms that enables cancer cells to evade apoptosis.”

How resistance becomes inherited

It is known that tumors that regrow after radiation therapy often become more aggressive and more resistant to treatment.

“We wanted to understand whether resistance to death is inherited by the descendants of death-resistant cells that survived the initial irradiation,” Arama says. “We found that when the same tissue is irradiated a second time, the number of cells that die during the first few hours is half that seen after the first irradiation, and most of the dead cells belong to the NARE population. In other words, the descendants of DARE cells were found to be exceptionally resistant – seven times more resistant to cell death than cells in the original tissue. This may help explain why recurrent tumors become more resistant after radiation.”

A delicate balance between tissue repair and excess growth is essential to any regenerative process. In the final part of their study, the researchers revealed how uncontrolled growth is prevented during tissue repair after injury. “DARE cells promote the growth of nearby NARE cells, apparently by secreting growth signals,” Arama notes. “In turn, NARE cells secrete signals that inhibit the growth of DARE cells. In fact, we’ve discovered a negative-feedback loop between the two cell populations that prevents overgrowth.”

“We hope that, as has often been the case with fly models, the knowledge gained here can be translated into an understanding of the mechanisms that balance growth and confer resistance to cell death in human tissues,” Arama concludes. “Many cancers originate in epithelial cells that have lost normal growth control, and many traditional cancer treatments aim to cause them to self-destruct through apoptosis. Our findings pave the way for understanding why such treatments sometimes fail and how they could be improved. The results also point toward new ways in which we might be able to accelerate beneficial regeneration of healthy tissue after injury.”

Reference: “Apoptosis-resistant cells drive compensatory proliferation via cell-autonomous and non-autonomous functions of the initiator caspase Dronc” by Tslil Braun, Naama Afgin, Lena Sapozhnikov, Ehud Sivan, Andreas Bergmann, Luis Alberto Baena-Lopez, Keren Yacobi-Sharon and Eli Arama, 4 December 2025, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65996-2

This research was supported by a grant from the Israel Science Foundation (grant No. 1378/24) and a grant from the European Research Council under the EU’s Seventh Framework Program (FP/2007-2013)/ERC grant agreement (616088).

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.