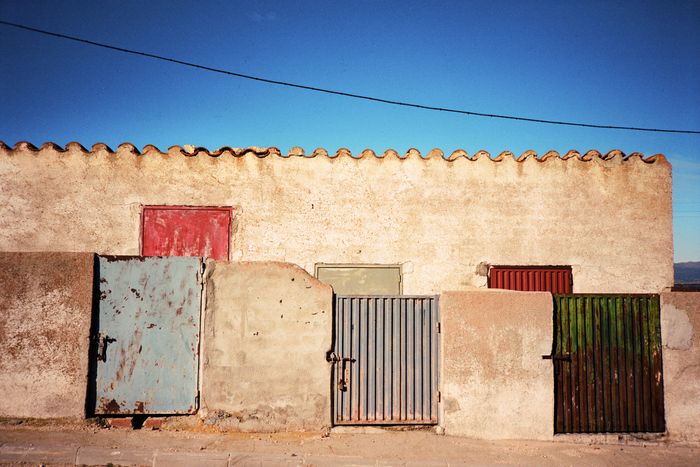

Photo: Francesc Planes for The Cut

When I first visited Spain in 1979, the country had recently become a democracy and General Franco, its dictator since the 1936–39 Civil War, had been dead for four years. Not that I was conscious of any of this. I was 23 and had never been to Europe before. I had with me a copy of George Orwell’s memoir of the war, Homage to Catalonia, a going-away present from a friend. I read it on the night train from Madrid to Barcelona. The next day, I looked up the places he mentioned — the hotel Continental, the Café Moka, the cinema with its twin domes. They were still there. Which, in Europe, hardly proved anything; shabby landmarks existed everywhere. But I just felt lucky. Being there, I understood that what Orwell described had really happened. They were real events. And this was also his point: “It is difficult to be certain about anything except what you have seen with your own eyes.”

Forty-six years later, on October 18, I was back in Spain, wandering around elegant Madrid, and I could only marvel at this modern democracy, its confidence, its wealth of small shops, and an economy said to be the envy of Europe. That night, at the restaurant El Pescador, I met a young woman named Anne, a lawyer from Geneva. Anne had been reading Thomas Schlesser’s Mona’s Eyes, a novel about a girl who may be losing her sight and so is taken to a museum every week to see a different painting. Anne and I talked and talked — about Spain, travel, people we knew in common (small world!) — as the guys behind the bar passed us plates of crab and langostino. I’ve met some amazing people in my life but rarely have there been encounters that gave me that deep, buzzy sense of joy, a connection to the murmuring spirits. And twice now it has happened in Spain.

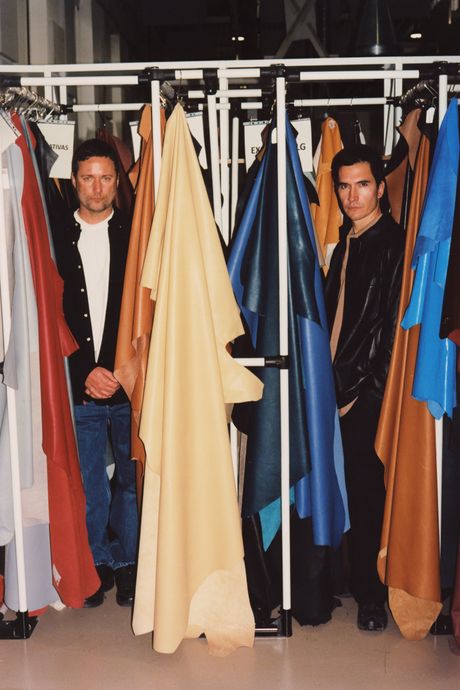

That delight is what I was looking for. In two days, I would embark on a journey with Lazaro Hernandez and Jack McCollough, the American designers who in April 2025 had moved to Paris to become creative directors of Loewe. For months, I’d had the idea of taking a designer on a two-to-three-day road trip for the purpose of writing about what they see. Designers create things that transform our eyes. What attracts theirs?

For Lazaro and Jack, a couple since their junior year at Parsons, this is a thrilling time in their lives, a chance to radically shift their perspective to Europe after decades in New York, where their freewheeling brand, Proenza Schouler, made them press darlings. Given Loewe’s prestige and size, it’s also a high-stakes moment for the 47-year-old designers. Over the years, I’d heard them talk about wanting a new challenge, how running their own brand, while gratifying to an extent, had become a routine. “We were so numb that we’d walk down the street not looking at anything but just kind of staring at our phones,” Jack said. Since settling in Paris, where Loewe, a Spanish company established more than a century ago, has its design studio, they feel their eye, and creativity, has been reawakened. “Walking around,” said Lazaro, “we’re like, ‘Look at that coffee place, look at that color, look at that girl wearing that jacket.’ ” They got an idea for their debut show, in early October, from a red-and-white signal they saw on a Seine bridge; its geometric design reminded them of the color-field paintings of Ellsworth Kelly. That inspired them to combine an American minimalism with a Spanish sensuality, told in vivid color.

Photo: Francesc Planes for The Cut.

Photo: Francesc Planes for The Cut.

At Loewe, they have access to materials and artisans they never fully did before. Yet they are much less free to explore — to simply look around — because of the heightened demands on their time as creative directors of a global brand: eight collections a year, four shows, accessory design, fragrance concepts, and directing ad campaigns and marketing. At Proenza, Lazaro and Jack sketched every garment themselves; they chose the fabrics and did all the fittings for shows. At Loewe, they now have a team of around 60 designers. Their job is to provide creative direction for the season in the form of a verbal brief with visual references, then guide teams through the completion of that brief. “That’s been the hardest part of this whole thing,” Lazaro told me. “The scope of the work is such that everyone in a high position has to learn the art of delegating.”

The nonstop collections and shows aren’t the only reason the industry doesn’t exactly allow for escape. Designers and their teams have grown used to exploring digitally — that is, finding their ideas online or by scrolling Instagram. It’s no secret that a lot of new fashion is created from existing images, be it a flapper’s beaded dress or a Japanese kid’s carefully destroyed jeans. The system is the inevitable outcome of modern technology and the need for greater productivity — to keep putting new products in front of consumers.

So Lazaro and Jack were eager to hit the road in Spain, a country whose art, crafts, and culture have been reflected in Loewe’s eclectic designs, notably those of their predecessor, Jonathan Anderson. They had previously visited Madrid and vacationed in the Balearic Islands. We planned to meet in Madrid on October 20 and drive to San Sebastián and Bilbao via Segovia. Our itinerary, which Loewe’s office helped put together, included three museums, a garden, a winery, a glassmaking factory, cultural landmarks, and the promise of delicious food.

Clearly, this was a lot for a three-day road trip. But you can’t deny the value of observing things firsthand. Seeing surfers in San Sebastián walking through town at dusk with their boards, blending with well-dressed people out for a stroll, is very different from looking at a picture of them. It’s the difference between reality and abstractness, between the unique and the secondhand. In other words, you wouldn’t believe the magic of a scene unless you had seen it with your own eyes.

Photo: Francesc Planes for The Cut

On Monday morning, shortly before nine, I set off from my hotel in our Hertz rental, a dark-gray Mercedes sedan, toward the opulent wedding cake formerly known as the Madrid Ritz, where Lazaro and Jack were staying. I managed to whiz down the Paseo del Prado without incident and found the guys in the hotel lobby. Their personalities have hardly changed since I first met them two decades ago: Jack is teasing and ironic, Lazaro more emotional and wired. After some chitchat, we walked across the road to the Museo del Prado, where Loewe had arranged a private tour of the galleries, followed by a visit to the restoration workshop.

Our museum guides greeted us and then led us to the central gallery, hung with old masters. On the ground floor, we stopped in front of The Garden of Earthly Delights, by Hieronymus Bosch. Not only did we have Bosch to ourselves but, for the next hour, all the galleries comprised by the royal collection of Spain, a staggering representation of wealth, power, and morality.

“You really feel the weight of Spanish history,” Lazaro said to me as we drifted into a roomful of work by Diego Velázquez and paused before the mysterious Las Meninas, his portrait of the young daughter of Philip IV in court dress with an odd cast of extras, including a chaperone dressed like a nun, a dwarf, a dog, and Velázquez himself, brush in hand. When Anderson was creative director of Loewe — a role he held for a dozen years before moving to Dior in 2025 — he often drew upon old masters, not only Spanish but Dutch and English. A Puritan collar, a balloon sleeve, indeed a side-hooped dress not unlike the little girl’s could migrate into one of his collections, creating a tension of references that made Loewe a conceptual brand. Lazaro and Jack mostly asked questions of our guides and kept their other thoughts to themselves.

We took an enormous freight elevator up to the restoration rooms. The whole area, with high ceilings and arched windows, resembled a modern painting studio, except that the canvases were by, among others, El Greco. Almudena Sánchez, a restorer, was using a tiny brush on an extremely tall El Greco to remove layers of old varnish. She might work on a piece for a year.

Later that day, when I asked Lazaro and Jack what they took away from our visit, Lazaro said, “The history is major, but what I’m pulling about Spain hasn’t anything to do with the Prado. It’s more the woman who was showing us around, the way she kissed on the cheek and gave us a hug before we left. That, to us, is Spanish — this intimacy, this warmth, this openness.” They were also struck by the skill of Sánchez, not to mention her patience. As Jack said, “We never have a lot of time with anything we touch. We’re always moving on to the next thing.”

We stopped for a lunch of jamón ibérico and grilled sole at Filandón, on the edge of the city, and it was after four when we got on the road to Segovia, where we planned to stay the night. We had just begun to ascend the Guadarrama Mountains, a modest range densely covered with pine and oak, when Jack, from the back seat, said, “Jodie says, ‘I bet Cathy is a good driver.’ ” He was tethered to his phone and thus to Jodie Barnes, the stylist.

“I can’t imagine why he’d think that,” I said brightly. The switchbacks were starting to make me nervous.

We were glad, though, to finally be going somewhere. As we climbed and climbed, the views were spectacular, lush green, and the car filled with talk of travels and the boys’ impending move to an apartment in Paris; they’d been living in temporary quarters. From time to time, they would be on their phones sending texts. It was hard for them to disengage from the studio, and I guess I didn’t expect them to. They explained that in addition to their next show, in March, they were working on their first-ever men’s line and getting ready to shoot their spring-summer campaign in Rio de Janeiro. At this stage of their careers, and with so much riding on everything, they couldn’t afford to pretend they were out for a lark, Thelma and Louise on the Castilian plain. “We don’t typically have three days free,” Lazaro said. “Like, my mom doesn’t get three days anymore.”

Despite careful planning, it was clear we had overbooked our day. To reach Segovia in time to wander around before dark, we had to cancel the garden tour and hurry through the glass factory, where a charismatic young woman in dungarees took Lazaro through the steps of making his very own bottle in an ancient oven. We did manage to catch a glimpse of a lovely square in old Segovia in the shadow of its famous Roman aqueduct, but it was from the car — and then a policeman let us know we were in a pedestrian-only area. I zoomed out of the square.

Minutes later, we were settled at a table at the charming Mesón de Cándido, where photos of celebrities adorned the rustic walls, along with game trophies and rifles, and the specialty is suckling pig. As we began a bottle of Rioja, the waiter put down a platter of cured ham, our second or third of the day.

For years, the designers had felt, as Lazaro put it, “the gravitational pull of Europe” in the fashion conversation — during a period when the New York industry was losing relevance and attracting few European journalists and buyers to the shows. Then, in 2024, Lazaro and Jack received a message from Delphine Arnault, the chief executive of Dior, asking if they planned to be in Paris anytime soon. They flew over the next month. At their meeting, Arnault, who is also a director of LVMH, which owns Loewe, was reticent about the group’s hiring intentions, no doubt because a major talent shuffle was unfolding across the industry. In time, for example, Chanel would hire Matthieu Blazy; Versace, Dario Vitale; and Anderson would go to Dior, a move that might have been in the works when the Proenza designers met with Arnault.

One thing foreign to them was the extent to which large studios use technology to create. “Among the younger designers, no one really draws anymore,” Lazaro said. He pulled out his phone to show me some images of works in progress. “They use Photoshop. Some use AI. And you don’t know what’s what. It’s all presented to you in these lifelike pictures. It’s quite insane.”

Jack said, “They do styling exercises with vintage archive pieces on a model and photograph them. And then they’ll put them into Photoshop and adjust them. Often, they put it into AI, give prompts to tweak things, and then put it back into Photoshop. I mean, it looks like finished garments.”

By telling AI to make a coat longer or the shoulders smaller, Lazaro said, the team “can give us 20 iterations of an idea. It’s crazy.”

“It’s scary,” said Jack.

Lazaro shrugged. “It’s speed.”

Hearing them talk about this system, I didn’t get the sense they were passing judgment on it. They were just intrigued by a different method of working. But I also understood why Lazaro said, a moment later, that it will take time for him and Jack to establish trust, along with a shorthand for working, with the team, which they inherited from Anderson. “So what the team knows is maybe not what we want,” Lazaro said. In other words, they can’t assume the team will understand their style preferences automatically. As their debut show made clear, they intend to keep some of Loewe’s conceptualism — for instance, they ingeniously referenced the artist Klara Lidén’s stacked and frayed “poster paintings” for a series of multi-layered cotton shirts. But they also want a more real sense of clothing based on the fundamentals of cut, proportion, silhouette.

“We’re not good with words,” Lazaro told me. But in their debut collection, they found what they wanted to say in the simplicity of jeans and a T-shirt, in the warm tones of a Spanish summer, and with leather pieces crafted so that almost no technique showed — like a Kelly painting. The reviews were probably the best of their careers.

Our waiter had returned, and Lazaro said to Jack, “Oh, wow, look at the pig behind you.” There, on a platter, lay a small tawny pig. We paused to admire it, and then the waiter did something peculiar. He took a salad plate and plunged the rim into the papery rind, scooping out the meat.

“I don’t think they put the head on your plate,” Lazaro said.

“I really hope not,” said Jack.

Photo: Francesc Planes for The Cut.

Photo: Francesc Planes for The Cut.

The next morning, we set off for San Sebastián, our longest drive: about four hours. The landscape soon turned from hilly and green to flat and arid under a broad sky streaked with clouds. “It’s like driving across the U.S. for the first time,” Jack said. “You see how dramatically the country changes.”

Frankly, for long stretches, there wasn’t a lot to see. The boys occupied themselves with texts; according to Jack, the office was “stressing out” because meetings needed to be rescheduled. Lazaro, in the passenger seat, nodded off for a bit. While we were happy to view art and Spanish craftsmanship, I think we were all eager to get away from our itinerary and just wander.

We agreed that we had to reach San Sebastián and the coast as quickly as possible. None of us had been to the Basque city before. We shelved the winery. At Miranda de Ebro, I got off the freeway and we stumbled upon a tiny bar, La Roca, crowded with people working their way through hamburgers and baskets of cheese croquettes. “It feels very road trip,” I said to Jack. He nodded. “I think we chose well,” he said. We did keep an appointment at Chillida Leku, the private museum of the late artist Eduardo Chillida Juantegui, where, on his country estate near San Sebastián, his sculptures are displayed on the lawn and fields. When we pulled out of the parking lot, it was already after 5 p.m.

Then, suddenly, everything changed. We made two or three turns and stretching before us were the golden-beige fronts of the town’s majestic buildings and the Urumea River running straight out to the sea. We dropped our bags at the hotel and headed to the quay to join other people out strolling. It had recently rained, and the sky was filled with dark, puffy clouds that diffused the light. The boys put away their phones.

Meanwhile, big rollers were coming up the river, breaking on the rock pilings and sending water up on the quay. We saw two or three surfers walking nearby with their boards.

“It’s so cool,” Jack said, grinning. “Surfers in cities. It’s such a strange combo, such a good vibe.”

We crossed the road, and for the next hour or so it was “Let’s look down this street,” “Let’s go here,” as we meandered through the old part of town, drawn by lights, the oddities in shop windows (one store sold only toy ducks, another chic nautical gear), and the hum of people at café tables. “You get a sense of the community living here,” Jack said. “And it feels like we’re discovering something — not what you find in, say, Florence or Madrid.” We went into a store specializing in cheese, honey, and seemingly every kind of sardine and anchovy. Lazaro picked up a block of goat cheese and put it to his nose. “Smell that!”

Looking around the shop, and really beyond, he added, “What do you take aesthetically from this, on a design level? What do you pull from this world?”

“A richness of life?” I said.

“Totally.”

A few minutes later, as we stood outside a bar having a drink before dinner — at Narru, one of the restaurants that has put San Sebastián on the international food map — Lazaro, thinking more about what we saw, said it would be a mistake to translate Spanishness too literally at Loewe, which, after all, is a global brand. “Spain is more of a feeling,” he said, “and that’s harder to express. It’s a zest for life and the good things and not necessarily in luxury terms. It’s about the things that matter. Family. Food. Time.”

Our road trip officially ended the next day in Bilbao, where we visited the Guggenheim and its dynamic director, Miren Arzalluz. The boys were leaving for Paris that afternoon. I was staying on for a bit. While Lazaro was talking to Arzalluz, who is Basque, about life in Bilbao, I decided to go and look at Richard Serra’s The Matter of Time, his monumental spiral-and-ellipse sculpture.

There, I found Jack alone in a curve, studying the weathered brown steel. I watched him for a minute or two before he glanced in my direction. He said, “The walls almost look like leather. We should re-create that patina for a beautiful bag. An oxidized leather.” He was so pleased.

It’s funny: all the times over the years that he and his partner must have walked in Manhattan and Brooklyn and seen rusty walls and not thought of a thing.

Photo: Francesc Planes for The Cut.

Photo: Francesc Planes for The Cut.