Issue 39, Winter/Spring 2025

Abstract

This article uses the Hierarchy of Influences model (Shoemaker and Reese 1996; 2014) to analyze results of a 2021-2022 study of science journalism in Qatar. The study extends the HoI model by incorporating the role of corresponding and contradictory interests when assessing findings across the five levels of the model. Empirical data were collected in semi-structured interviews with 15 Qatar-based journalists and editors. The findings clarify perceptual, structural and operational factors that influence the production of science journalism content in the context of news production more generally from a perspective rooted in the field of media management and economics. The findings provide insight on how newsrooms function in Qatar, the impact of financial and audience factors, and the practice of ‘churnalism’; importantly, they also form the basis for recommending a reconceptualization of news products as multi-market goods instead of the more common description of them as dual market goods.

Introduction

Science journalism in the Global South remains under‑theorized and under‑documented even as questions about how newsrooms allocate scarce resources, manage risk and negotiate boundaries continue to grow (Nguyen and Tran 2019; Tran and Nguyen 2023). Qatar offers a relevant case to advance theory related to news production. It is a small, wealthy rentier state with a highly cosmopolitan population and a concentrated media market in which print newspapers are, although privately owned, linked to state actors and elite stakeholders (Galal 2021; Kamrava 2013). While science journalism is widely acknowledged as having importance in Qatar’s national development strategy, editors and journalists we interviewed deemed it resource‑intensive, commercially uncertain and, therefore, unattractive due to a perceived lack of interest among readers (Mohsin, Nguyen, and Lowe 2025). Importantly, the practice of science journalism in Qatar reflects broader patterns of news production in the country that reveal editorial priorities, journalistic routines, and stakeholder negotiations over coverage. The Qatar context provides an empirical window to investigate how political and economic considerations shape editorial decision‑making and professional routines that demonstrate corresponding and contradictory interests.

This article applies the Hierarchy of Influences (HoI) model proposed by Pamela Shoemaker and Steven Reese (1996; 2014) to analyze findings from a 2021-2022 study of science journalism in Qatar. We seek to extend the model by focusing on media management to center attention on stakeholders’ corresponding and contradictory interests within and across the five levels of analysis using the model. We believe analysis using the model benefits from consideration of motivations that drive influences. We go beyond applying the HoI descriptively by incorporating situated interests as an intersection of motivations and concerns, drawing on the work of Renninger and Hidi (2015). We examine their interaction across the five interdependent levels of the HoI model: individual, routines, organization, external institutions, and the social system.

The findings indicate editorial decisions about science coverage in Qatar are keyed to two essential pressures: (1) economic constraints caused by declining audiences that account for dwindling advertising and subscription revenues which is a concern more or less everywhere (Picard 2016; Nielsen 2019), and (2) political expectations for news coverage that encourage prioritizing official sources, event‑based reporting, and editorial risk‑avoidance due to dependency relations with governing authorities. The latter is not unique to Qatar (e.g., Dragomir and Söderström 2022; Hallin and Mancini 2004).

Nguyen and Tran (2019) conducted extensive research on science journalism in the Global South and documented challenges that can be summarized as five recurring constraints: an overreliance on sources in the Global North; the marginal status of domestic science news; reporting that lacks critical analysis and sufficient contextualization; political influences on editorial policies and practices that affect science journalism (and news production more generally); and weak collaboration between scientists and journalists. As financial resources tighten and readership declines, news outlets in many countries increasingly rely on churnalism, the routine of publishing minimally edited press releases as news (Harcup 2004; Davies 2008). The practice reduces costs but erodes journalistic distinctiveness (Jackson and Moloney 2015). Our interviewees in Qatar described churnalism as a default routine for publishing news across genres, including science.

The Qatar press developed late and remains small, with titles typically owned and/or overseen by elites with close ties to the ruling family (Galal 2021). Of the eight newspapers in Qatar, all based in Doha, two are online-only: Al Arab (launched in 1972 then relaunched only online in 2007) and Doha News (established in 2009, English-only). The other six newspapers are three broadsheets with sister editions in Arabic and English: Al Raya and Gulf Times, Al Sharq and The Peninsula, and Al Watan and Qatar Tribune. These titles are linked with members of the royal family (Galal 2021, 137). For our study, we analyzed the six print newspapers—three in English and three in Arabic.

The management structure of Qatar newsrooms is hierarchical. While not unusual, in Qatar the senior editorial roles are reserved for nationals while the majority of journalists are expatriates, largely from the Global South (Kirat 2016). Although formal guarantees of press freedom are codified, legal ambiguity and bureaucratic gatekeeping produce a cautious newsroom culture in which official invitations, events, and press releases underlie the coverage routine. Within this ecosystem, newspaper editors balance audience expectations, advertisers’ interests, and the rules and preferences of authorities under conditions that prioritize financial considerations and political sensitivities. This case illuminates macro-level forces in the social system of the HoI model while revealing micro‑level tactics that editors and reporters use at the individual level to reconcile self-censorship with professional norms at the organization and routine levels. Here we address three linked questions:

RQ1. How do political and economic considerations shape editorial decision‑making about science journalism in Qatar when analyzed through the HoI framework?

RQ2. How do corresponding and contradictory interests manifest across HoI levels, and with what consequences for routines (such as churnalism, the allocation of resources and managing risk)?

RQ3. What empirical evidence supports reconceptualizing news content as multimarket goods in Qatar, and what implications does this have for research in the field of media management and economics?

This article draws on semi‑structured interviews with fifteen journalists and editors working for Qatar‑based news outlets, mostly newspapers, as part of a broader research project that included content analysis of local news coverage (N=429), a Delphi panel with local scientists, and a series of focus groups with important population segments. We focus on the interviews to analyze how interests manifest across HoI levels and how related dynamics shape science coverage. A more comprehensive treatment of research results has been published elsewhere (Mohsin, Nguyen, and Lowe 2025). Access constraints and the small size of the Qatar market necessitated using a convenience sample and snowballing technique for the interviews.

In our analysis, we found that editor decision-making in Qatar newsrooms reflects the politics and power paradigm for strategic decision making (SDM) that best captures the challenge of balancing between stakeholders with overlapping and contrary interests keyed to variation in motivations (drawing on Eisenhardt and Zbaracki 1992). The task of strategic decision-making is about both the reasoning of choices and how a decision has been negotiated. What is feasible is usually more important than what is optimal. In this paradigm, “individuals may share some goals such as the welfare of the firm, [but] they also have conflicts … that arise from different bets on the shape of the future, biases induced by position within the organization, and clashes in personal ambitions and interests” (23). Every organization is political in practice, if not identity.

The findings generate fresh insight on the nature of news content and shed light on how editors make decisions about news production in a hybrid regime–a term used to describe a state that is autocratic but exhibits variable democratic aspects. Based on our findings, we think the context encourages reconceptualizing the concept of media products as ‘dual market goods’ which focuses on balancing the interest of audiences and advertisers in commercial media firms to multimarket goods in contexts where authorities act as a third influential stakeholder. In our view, ‘multimarket goods’ usefully captures the persistent, often complex challenge of balancing the interests of audiences, advertisers, and authorities, which can correspond (e.g., celebrating national R&D achievements) or contradict (e.g., critical coverage of sensitive scientific topics) depending on the issue, timing, and perceived risk.

In the following sections, we explain the theoretical framework, describe the methods and analytic procedures, present findings mapped to HoI levels highlighting cross‑level interest dynamics, demonstrate the usefulness of the multimarket goods concept, and conclude with a discussion of implications and limitations.

The Hierarchy of Influences model

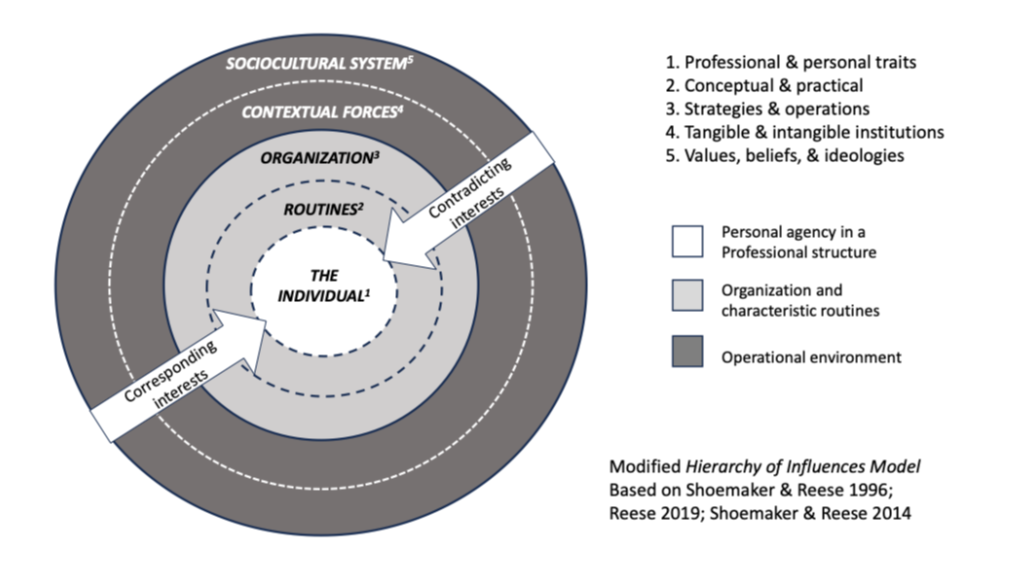

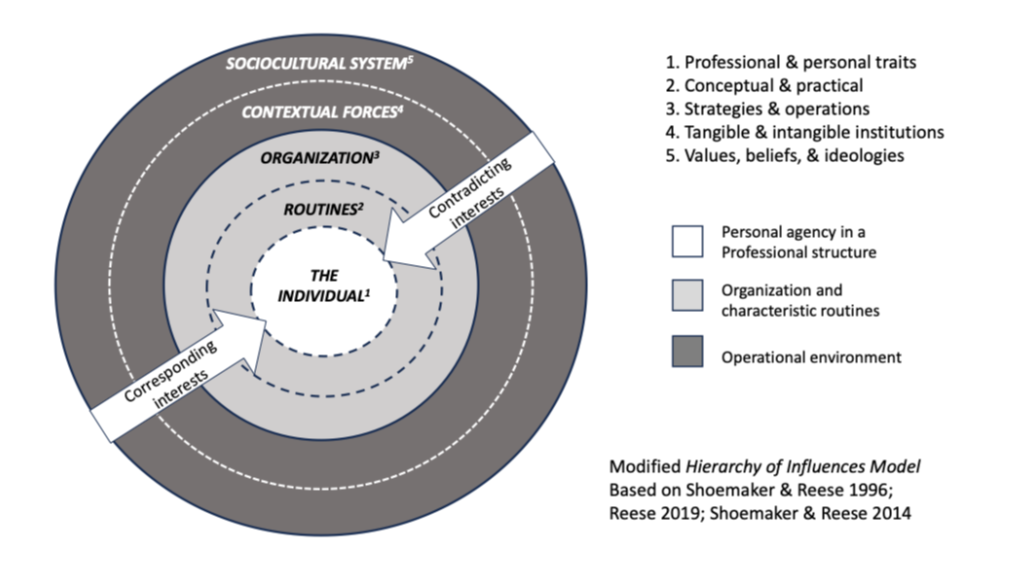

Shoemaker and Reese (1996) developed a social constructivist perspective on content production that encourages investigating influences across five interdependent levels of analysis. Many influences are ingrained in individuals via professional socialization in varying sociocultural contexts. We find the HoI model useful for improved understandings of why media makers and managers produce the content they distribute. The initial description of the model had inconsistencies that Shoemaker and Reese addressed in a 2014 update. They initially characterized the levels as a continuum, which does not imply a hierarchical structure. In the 2014 edition of Mediating the Message, they portray the model as an integrated system of levels or layers, with the two terms used interchangeably. Here, we use levels. Reese described the levels “as a set of concentric circles” with the individual at the core (Reese 2019). However described, the essential point has been consistent: “What happens at the lower levels is affected by, even to a large extent determined by, what happens at higher levels” (Shoemaker and Reese 1996, 9). In this article, we conceptualize the model as pictured in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Hierarchy of Influences model applied in the current analysis

The shading of levels spans from the individual level at the center (unshaded) to the organization where routines operationalize strategy and tactics (thus sharing the same shade), to the external environment where contextual forces and the social system exert pressures on the organization and individual (thus sharing a darker shade). The dotted lines that separate levels suggest the porous nature of their interactions and dependencies. Corresponding and contradictory interests span the five levels and influence how individual professionals in different roles and positions interpret interests when decision-making has strategic implications. Decisions that court a degree of risk that matters for the firm’s and/or the individual’s future situation may be considered strategic. The individual has agency that is affected by external actors that the 1996 version described as extra-media and the 2014 version characterizes as institutional structures. We understand these to be ‘contextual forces.’ Agency and structure are embedded in a social system. These modest modifications are useful for analyzing interests that animate influences.

Content production is governed by professional paradigms that vary across genres and social systems understood as sociocultural contexts. Paradigms are operationalized in routines typically treated as norms among practitioners. Routines are instilled through formal training and informal influences in processes of professional socialization; they are structured by the nature and needs of the employer organization and subject to contextual affordances and constraints. Professional paradigms are neither uniform nor stable; they vary across space and time and are continually evolving in a reflexive relationship with contextual forces in a given social system with diverse domestic and international influences. Norms and routines are largely taken for granted in daily practice, to an extent that we may “lose sight of the fact that beliefs and expectations – and therefore paradigms – change not only over time but from one cultural environment to another” (Shoemaker and Reese 1996, 15).

In the 2014 edition of Mediating the Message, Shoemaker and Reese address three common criticisms of the HoI model. First, it has been criticized for over-simplifying the complexity of relations across levels that are different units of analysis. Critics have also argued that relations between the levels are more reflexive than hierarchical. Shoemaker and Reese acknowledged these issues but observed that every model must simplify to be useful for research and noted that how the model is applied depends on the researcher and purpose. They encouraged further research to “determine the conditions under which certain factors are most determinative and how they interact with one another” (2014, 12).

Concerning the second criticism, the authors acknowledged their model was premised on values that are largely taken for granted in American culture, especially the primacy of individual agency. They further noted that HoI research has mainly focused on Western media contexts, a pattern that has not significantly changed in the past decade (Collins, Kinnally, and Sandoval 2023). Because “media content is fundamentally a social construction” (Shoemaker and Reese 2014, 4), more insight is especially needed on non-Western contexts. Research is sorely needed to “help us understand differences in the way journalism is practiced in the West as compared to elsewhere,” and to “distinguish journalism in some parts of the non-Western world from other parts of that world” (Collins, Kinnally, and Sandoval 2023, 100). This appraisal links to the third criticism. Critics have observed that although the organization level is internal, boundaries between external and internal influences are fluid and elastic. This has implications for theory, which we approach in making a case for news content as multimarket goods due to the porous nature of boundaries between levels of the HoI model.

In our literature review, we found a gap in research using the HoI model hinging on lack of published research to improve understanding of the interaction within professional cultures. Therefore, we add a fourth criticism that is especially pertinent to our application of the model: Researchers need to focus some attention on what motivates the influences that are exerted. We tackle this by focusing attention on corresponding and contradictory interests. In the HoI model, an individual makes content and is therefore positioned at the center. Content makers are subject to many and varied influences, both conscious and unconscious, conditioned and situational, that co-determine what is and is not considered newsworthy, as well as how stories are prioritized and reported. The individual journalist is affected by influences encoded in professional standards, embedded in routines, and operationalized by organizations, all of which are influenced by managerial and economic forces that are not dealt with in much detail in the original model.

The authors define routines as “patterned, routinized, repeated practices and forms that media workers use to do their jobs” (Shoemaker and Reese 1996, 100). Professional routines both enable and constrain individuals in systemic and systematic ways that encourage predictability of performance. In each sociocultural system, there will typically be more similarities than differences across organizations in the same industry because routines are procedures that have been developed for production work to address characteristic needs and challenges. Professional routines enable makers to coordinate everyday practice. Shoemaker and Reese define the organization as “the social, formal, usually economic entity that employs the media worker in order to produce content” (1996, 138). Organizations have boundaries that establish membership, are goal-oriented, and tend to be bureaucratically structured. Organizational practices are governed by policies. The operational context is populated by diverse stakeholders. For newspapers, these especially include subscribers, advertisers, sources, owners, investors, and government entities. Many of the external stakeholders have their own in-house departments to handle media relations. As Shoemaker and Reese observed, such official sources are often favored by journalists and editors for the ease of access they provide and the sense of authoritativeness they imply.

Our interviews with journalists and editors in Qatar indicate clear awareness of Western journalistic norms, professional values, and typical routines, and equal cognizance of local cultural realities that differ and matter greatly in the production of science news as a situated practice. Professional and national cultures interact in ways that can create tensions not only for practice but also for the professional identities and organizational roles of journalists and editors. That is an important reason why “journalism practices identified in Western contexts don’t necessarily transfer to other settings” (Collins, Kinnally, and Sandoval 2023, 108). Reporters work in professional environments that exert prevailing influences rooted in value systems that vary. Thus, “values have structural effects” because they “function as social controls” on individual perspectives and behaviors (Sylvie and Huang 2008, 62).

This was evident in research on political journalism in Egypt that applied the HoI model (Elsheikh, Jackson, and Jebril 2024). Most of the 20 journalists who were interviewed identified the same primary influences to a remarkable degree (Elsheikh, Jackson, and Jebril 2024, 3353). There was a shared tendency to produce low risk reports that editors found easy to approve because they did not “annoy anyone” in the political establishment and journalists routinely practiced self-censorship “as a self-precaution to avoid potential problems” (Elsheikh, Jackson, and Jebril 2024, 3360). Journalists and editors agreed that financial constraints encouraged producing “fast news” copied from press releases or posted on social media sites. These attributes at the organization level of the HoI model were linked to government involvement as the prevailing contextual force and was legitimated by a widely shared perception in the social system that journalists had an instrumental role in fomenting the civil unrest that led to the overthrow of two former Egyptian presidents: Hosni Mubarak and Mohamed Morsi. The authors argue this suggests the social system level is the primary source of influences (Elsheikh, Jackson, and Jebril 2024, 3361).

That point addresses a core question for the HoI model that hinges on uncertainty about the relationship between agency and structure: Does the individual or the social system exert the most influence? Shoemaker and Reese (2014) believe that although no level is primary for analytical purposes, the social system establishes constraints and affordances that contextualize what happens at individual and organization levels. They therefore suggested that the social system exerts hegemonic influence as societal elites in politics, business, and culture harness media to maintain a status quo that benefits them. They suggest analyzing the social system as the sum of four interdependent subsystems: cultural, ideological, economic, and political. The ideological element legitimates a generally shared set of values and normative beliefs which both constrain and enable acting in patterned ways. They further observe that economic and political subsystems have been found to strongly influence news organizations, managers, and makers everywhere the HoI model has been applied in research.

Interests and Strategic Decision Making

The complex assortment of interacting influences on decisions taken by managers is a characteristic interest of management scholars, as evident for example in Michael Porter’s five-forces model (1979), Henry Mintzberg’s alternative approaches to formulating strategy (Mintzberg, Lampel, and Ahlstrand 1998), Edgar Schein’s research (2016) on organizational change and development, and the work of Vijay Govindarajan and Chris Trimble (2010) on challenges in implementing innovation in organizations, to highlight a few. Within and across levels of the HoI model, the interests of one stakeholder may, to varying degrees, correspond or contradict with the interests of other stakeholders because organizations are internally complex with complicated external interdependencies.

Interests are self-defined at the intersection of motivations and concerns (Renninger and Hidi 2015). Research has posited three categories of motivation: intrinsic, extrinsic, and achievement. Intrinsic motivations drive engagement in pursuits one finds personally satisfying. Extrinsic motivations are enacted to obtain rewards or avoid punishments. Achievement motivation drives the pursuit of comparative success in a sociocultural environment, whether organizational or societal. Concerns are determined by one’s perception of potentially negative outcomes such as fear of failure, uncertainties that cause anxiety, a decline in well-being, or fear of being considered irrelevant. Motivations are drivers while concerns are perceived risks. An agent decides to act in a particular way in a specific context based on personal interests that are affected by the confluence of motivations and concerns. Hidi (2001) emphasized the importance of recognizing situational interests embedded in social environments. For any given policy, routine, or practice, an individual’s interests will align or conflict with the interests of others to varying degrees. We address this tension as a matter of corresponding and contradictory interests that both motivate the exercise of influence and are influences on interests.

Deciding what to cover and publish is the responsibility of editors. Strategic decision-making (SDM) is necessary when decisions have broad and/or longer-term importance. Eisenhardt and Zbaracki (1992) clarified three paradigms: (1) rationality and bounded rationality, (2) politics and power, and (3) garbage can. The rational paradigm supposes the decision-maker has clear objectives and relevant information needed to decide the best option. There are cognitive limitations and the problem of incomplete information, which explains the correlated concept of ‘bounded rationality.’ The ‘garbage can’ paradigm describes decisions made in ambiguous situations where and when there is limited or conflicting information. In such situations, decisions are based on conjecture and participation may be fluid and uncertain. In this article, we find the politics and power paradigm most useful.

SDM happens in an organizational context that blends perspectives, characteristics, and interests of managers with the firm’s identity and orientation in relation to the operational environment (Shepherd and Rudd 2014). The senior management team, in this case, editors and owners, decides priorities and parameters that govern decisions about what should and should not be covered, how, and by whom. The political and social context shapes professional identities and the roles of journalism, as well as the priorities, routines, and constraints that affect editors. George Sylvie, Seth Lewis, and Qian Xu (2010) conducted a study that compared editor values and related behaviors in the USA and Nordic region. They found striking differences and urged researchers to adopt a “cultural lens” when studying how editorial decisions are made. They observed that journalists make decisions that are conditioned and constrained by editors who, in turn, make decisions that are influenced by their roles and responsibilities in organizational and broader social systems.

As Ruth Moon observed, many journalists engage in self-censorship, which implies a strategic orientation. Moon described self-censorship as a negotiation process with three strategic options: 1) deciding not to pursue the story, 2) creating buffers for self-protection during the reporting stage, and/or 3) negotiating with managers and sources to guard against potential repercussions upon publication (2023, 121). Journalists navigate tensions between societal norms and constraints on the one hand and professional motivations and goals on the other. Negotiations are situated and contingent. Moon (2023) noted that journalists tend to “avoid explosive topics” that would endanger their lives or livelihoods, a strategy she characterized as “informed avoidance” (2023, 128).

Taherdoost and Madanchian (2023) proposed four decision types. Our findings make clear that for decisions taken by editors in this study, constructions and evaluations are most common.

- Acceptances: a binary choice between accepting or rejecting an option

- Choices: deciding what is best from a limited set of options

- Constructions: creating the optimal option based on available resources

- Evaluations: decisions based on adhering to principles and commitments

In summary, professional journalists and editors have agency to make decisions about content production that are informed by the norms and standards of the profession and influenced by a combination of personal and professional interests. They enact routines in organizations embedded in social systems and responding to contextual factors. Organizations are not homogenous in populations, roles, or perspectives. Internal views, opinions, values, and performances reflect personal agency that is influenced by corresponding and/or contradictory interests in relation to other stakeholders. The operational context is complex and multifaceted. Key stakeholders for newspaper companies include readers, advertisers, and government agencies (here characterized as authorities) within structural arrangements that are legitimated by systemic sociocultural features reflecting ideological dispositions. In our analysis of findings, we apply the extended HoI model to interview data about science journalism in Qatar from a perspective that highlights interaction within and between the levels and reflects the role of corresponding and contradictory interests.

Qatar

Qatar is a small, wealthy peninsula state with a highly cosmopolitan population characterized by Mehran Kamrava as “a rentier state par excellence” (2013, 130). In a rentier state, cohesion is maintained by distributing economic benefits, in this case significant income derived mainly from the sale of natural gas. About 13% of 3.1 million people in Qatar are citizens. The rest are expats from at least 150 countries. The population (80%) is concentrated in Doha, the capital city (Worldometer 2025). Due to a large population of guest workers, men outnumber women by 3:1 (Qatari Magazine 2025). The political system is a stable monarchy with a popular royal family. We characterize Qatar’s government as a ‘hybrid regime,’ a term that describes a political system with mainly autocratic features blended with some democratic features, for example municipal elections and for the Shura Council (a consultative assembly). This notion was introduced in the mid-1990s as an alternative to the traditional binary view of a political system as either authoritarian/autocratic or democratic (Bogaards 2009).

By Western norms, Qatar has a restrictive news environment. The official view (Amiri Diwan 2025) suggests that Qatar “scrapped censorship of the local press” in 1995 and abolished the Ministry of Information in 1998. The 2003 Constitution (Article 48) guarantees freedom of the press. The reality is more ambiguous. In 2024, Qatar was ranked 79th (Doha News Team 2025), which is the highest ranking in the Gulf region. Media law is a legacy of British colonial rule with vague, potentially unlimited prohibitions on public speech. A license is required to publish news and criminal provisions for offenses include libel. The 2014 Cybercrime Prevention Law No 14 of 2014 added fines and potential imprisonment for online offenses.[1]

Methods

This study draws on semi-structured interviews with 15 journalists and editors working in Qatar’s media industry (Table 1). The selection was a convenience sample. Qatar is a small market with a few news companies. Gaining access was facilitated by the researchers’ affiliation with Northwestern University Qatar and funding from the Qatar National Research Fund, both locally respected. We contacted many more professionals than agreed to be interviewed. Those who agreed were promised anonymity. Due to the small sample size and number of outlets, we have not specified who said what in quotes highlighted in the findings other than to describe the respondent as a journalist or an editor.

| No. | Gender | Position | Training | Organization at the time of interview |

| R1 | M | Senior Producer & freelance science journalist | Master’s degree | Private |

| R2 | F | Producer & general news reporter | Media institute | State-linked |

| R3 | M | Staff reporter with beats in education and IT | No info | Private |

| R4 | M | Senior editor | PhD | Private |

| R5 | M | Managing editor | University | Private |

| R6 | F | Researcher & freelance journalist | University | Private |

| R7 | M | Former editor and freelance journalist | University | Private |

| R8 | F | General news reporter | University | Private |

| R9 | M | Desk editor and reporter | Seminars & workshops | State-linked |

| R10 | M | Department director and trainer | No info | State-linked |

| R11 | M | Senior editor | University | Private |

| R12 | F | General news editor | Master’s degree | Private |

| R13a | M | Managing editor | Master’s degree | Private |

| R13b | M | Head of editorial section | Master’s degree | Private |

| R14 | F | News and content producer | University | State-linked |

Table 1: Overview of 15 interview respondents

The interviews were conducted between April and August 2022. Most required 30-40 minutes. A few lasted more than an hour. Respondents were interviewed in person or via Zoom, according to preference. Four interviews were conducted in Arabic by a bilingual member of the research team. All interviews were recorded with permission. The interview data was transcribed by Intelligence Qatar (IQ), a market research firm in Doha, which also translated Arabic transcripts into English. This was done by bilingual employees at IQ. At least two members of the research team participated in each English-language interview. The four interviews conducted in Arabic were conducted by one native speaker.

While we did not employ a grounded theory methodology, we systematically coded the interview transcripts to identify recurring themes related to journalism practices and the culture of Qatari news production. Coding was conducted collaboratively: team members independently reviewed transcripts, then met to discuss and refine the emerging themes. Through these discussions, we ensured inter-coder reliability and reached consensus on the thematic structure, which was documented in the final project report submitted to the Qatar National Research Fund (QNRF) as part of funded-research contractual obligations.

It is important to note that we were not able to access figures on employment and revenue of Qatari news organizations because such data are not publicly available. Kirat (2016) provided a snapshot of the size and composition of the country’s journalism workforce. Additionally, our interviews offered qualitative evidence of financial constraints, as respondents frequently referenced limited resources and the challenges of sustaining specialized reporting such as science journalism. These accounts allow us to infer the economic pressures shaping newsroom practices, even in the absence of comprehensive organizational data.

Findings

We discuss findings that illuminate how editors and journalists perceive science journalism and the general practices of journalism in Qatar. We apply the HoI model and highlight corresponding and contradictory interests. Our qualitative analysis revealed patterns that facilitate extending the Hierarchy of Influences model by foregrounding the interplay of corresponding and contradictory interests within and between levels that reflect the interplay of motivations and concerns. This extension reflects complex negotiations that shape editorial decision-making and govern newsroom routines in Qatar.

Science news is important but considered commercially non-viable

At the individual level, respondents acknowledged the importance of scientific R&D in Qatar, but at the routine level there is little localization of science news (Mohsin, Nguyen, and Lowe 2025). National investment in scientific R&D exceeded US$1.4 billion up to 2022 (QNA 2022). Respondents reported no dedicated science desk in Qatar’s print outlets. This signals contradictory interests between the organizational and social system levels of the HoI model. Most journalists described themselves as generalists with limited training in science. One said, “I’ve hardly met any journalists who are that specialized [in science reporting]. It’s just not financially viable. As a journalist, when you work in an organization, they expect you to be multi-skilled.” There was one self-identified science journalist who worked freelance.

The low prioritization of science journalism was linked to perceptions of low popularity among audiences that discouraged investing in the genre. Few respondents considered science news interesting for most readers. One journalist explained, “It’s one of the things that we unfortunately do not cover much because whenever we work on such topics, we realize that some of the audiences are not engaging well with them.” Another observed that only an elite sliver of readers are “engrossed in reading science stories – mainly professors, researchers, and doctors.” An editor said, “For the majority of the audience, science is nothing. There is no widespread interest.”

The perceived lack of public interest in science news (see Mohsin, Nguyen, and Lowe 2025; Piryadarshini 2025) had financial implications for editorial decision-making. A journalist explained:

A lot of newspapers and news organizations don’t want to invest in science journalism because they don’t see an audience for that. I understand from a financial point of view. It’s hard to invest in something where you don’t see the return on investment. There’s just no revenue for it. And we have competing resources because there are other trending things that we have to cover. There’s only so many of us in a team… I guess the main thing is what value this will bring to our news company? I think that’s what every manager would want to know.

While we found contradictory interests between the organizational and social system levels of the framework, editors and journalists had corresponding interests. Journalists commented on the amount of work required to report on science. One explained, “I can do a piece about history or politics in two to four days. It takes a week to ten days to do a piece on science.” Editors described science news as a potential money pit. One asked, “What type of science? Newspapers cannot employ people who are qualified in all these topics. How many science journalists are you going to employ?” Costs were also associated with training journalists to improve science literacy. A journalist observed, “Science reporting definitely needs a lot of training… [and] you need to update yourself about what is happening around you and the world on a daily basis.” Several journalists said the lack of adequate training made them hesitant to cover science issues.

We found corresponding interests between journalists and editors at the individual level. While motives varied, as editors were mainly concerned about financial aspects whereas journalists were primarily preoccupied with the workload and potential for mistakes that could have consequences, all agreed that reporting on science is expensive with uncertain commercial value. Respondents uniformly acknowledged the importance of scientific R&D in the national context, but questioned its commercial viability as news. The findings, therefore, also indicate contradicting interests between national policy and investment at the social system level and routine practices at the organizational level that affect production processes for individual professionals.

The churnalism routine

Churnalism describes the routine of publishing press releases as news stories (Harcup 2004; Davies 2008). Respondents agreed this is common in Qatar’s newsrooms. One journalist lamented, “This is one of the big problems in Qatar in general. News journalists will just take the [release] as it is and report it that way.” Another journalist said that stories in Qatar are “generally based on press releases… our job here is just to do editing.” Respondents said churnalism is practiced in most genres of reporting, including science.

One journalist described an experience he construed as typical. While attending a conference about medical research, he observed, “Everyone was busy but not working. No one was writing anything. No one really writes. They know… the PR company will send them a press release. He can take the press release and put it on the website. That’s it.” Another respondent was bothered by this tendency: “The sad thing is the media wait for somebody to come to them. They wait for a press release or they wait for a media organization to contact them. That’s when they do the story.” An editor said his newspaper receives press releases routinely and publishes most with minimal editing because it is cheaper and faster than producing original stories. Some respondents expressed concern about churnalism in Qatar, and one editor drew a sharp distinction: “The journalist is important to me; the PR is not important to me. Public relations doesn’t know the difference between fabricated and real news.” However, another editor said he approves many stories with minimal editing as a necessity for speedy publication.

Both contradictory and corresponding interests are evident in findings that pertain to the churnalism routine. Opinions were divided as to whether such practice is appropriate for professional standards. As observed, while some editors were concerned about the professionalism of PR journalism, it was generally justified as an approach needed to manage scarce resources. Some journalists who criticized the practice nonetheless followed the routine to avoid excessive workloads and potential mistakes. At the organization level, financial constraints were augmented by political considerations that encouraged editors to prioritize other types of coverage, typically stories involving Qatar’s leaders and events of presumed broad public interest. At the individual level, we found professional concerns about how this routine affects the value of published content and the perceived status of professionals. While the motivations for embracing or resisting the routine varied, concerns were generally shared. Criticisms of over reliance on press releases did not imply a lack of perceived value, however. As one journalist observed, “We need such [information] to come from a source everybody believes – a reliable source. It’s going to be from the government; the official channels.”

Journalists also struggle to collect Arabic language information about scientific research, and with challenges involved with translating scientific terminology into Arabic. One journalist provided a succinct overview: “In Arabic, it is a nightmare to find credible information that is scientific… [and] it’s so hard to translate terms. Sometimes we have to come up with a translation because there isn’t a certified one in Arabic. Then, we add the English term in case people want to search about this because if they search in Arabic they won’t find it.” The higher volume of work required to report on scientific research was thus compounded by the need to engage in translation. This point may be overlooked in critiques about the lack of local science news. The problem is compounded in Qatar’s highly cosmopolitan social system where most journalists are expats from non-Arabic countries.

Editors and journalists viewed training differently due to divergent priorities, reflecting contradictory interests as well. Journalists worried about being unqualified to report accurately on science, while editors worried about the costs for training to do that better and faster. But we found corresponding interests between external stakeholders in the social system and editors at the organization level who publish press releases as news, with varying amounts of modification. External stakeholders achieve publicity goals by issuing PR releases, and editors avoid complications and save on expenses by publishing them largely as-is. For editors, motivations are partly driven by risk avoidance and partly by concerns about efficiency. Risk concerns are related to potential complications in publishing news about sensitive topics in science – for example, research on sexual orientation or other ‘taboo’ subjects, publishing information that is factually incorrect due to lack of understanding the subject matter or translation errors, or information that would be frowned upon (at least) by authorities.

Navigating political realities

The data indicate significant influences from contextual forces at the social system level on the individual and organization levels. This confirms the 2014 view of Shoemaker and Reese. Political influences are at least as important as financial ones. Policies and structures affect what gets reported and how. This is not unique to Qatar. Today, relations are fraught between the American press and the Trump administration, for example. This tension is a thematic aspect of comparative models of journalism (e.g., Hallin and Mancini 2004; Christians et al. 2009) and has been treated in research on state intervention in public sector media (Dragomir and Söderström 2022). Political economists, in particular, focus their research on this area (e.g., Hardy 2019; Karlidag and Bulut 2020; Dourado et al. 2019).

The political structure is a contextual force in every social system that exerts substantial, if not always direct, influences on news production. It is a significant influence on strategic decisions taken by editors and affects guidelines for journalistic routines. However, one should not assume political structures are unified or consistent. There are typically fractures, contending positions and perceptions, and countervailing pressures that explain the need for ongoing negotiations, a focal interest of culture studies. As everywhere, journalistic routines are influenced by laws and governed by organizational policies keyed to legal requirements, as well as by informal but influential social and professional norms.

In Qatar, newspaper company senior editors are political appointees. As one journalist explained, “All editors-in-chief are political positions. They are appointed under certain conditions and according to a specific mechanism.” Another said, “The whole system is stacked in such a way that there’s an editor-in-chief who has to be a [Qatari] national, then there are managing editors who are expats.” As earlier noted, the vast majority of journalists in Qatar are expats, mainly from countries in the Global South. In Qatar, political influences are not opaque. Newspapers tend to be pro-government even when privately owned. It is important to observe that degrees and types of state intervention in news production vary across social systems, that prescriptions for best practices are normative, and that news organizations and journalists navigate political currents while pushing against constraints they seek to loosen.

Informal political influences were evident in the prioritization of official sources and interactions. One journalist described his experience with editorial decision-making: “They kinda steer towards a story where they will talk about an individual meeting with somebody [important]. All positive kinds of meetings or economy stories.” An editor explained the coverage routine includes consideration of VIPs who will attend, often officials: “when they invite us [to an event], I check the importance of the subject and based on the importance of the guests, we go for coverage.” Another editor explained, “We are ready to cover anything governmental… [although] we do not take any news and just publish. We rewrite it, but we do not take much time doing it because now, you know, media and journalism need speed.” This suggests that the two routines of coverage and churnalism are linked in practice.

A tension between professional interests to maintain journalistic independence versus organizational interests to not run afoul of authorities is evident in the data. For sensitive topics, deciding what to publish was described as a negotiation that is often informal, although not always. The decisions have strategic implications. An extended quote from an editor illustrates the complexity involved with navigating influences across levels of the HoI model:

There is always a conflict between pleasing the reader and pleasing the authorities. It is difficult to join them together. There should be a constant balance. In any situation we lean towards the reader or citizen. At the same time, we are careful not to adopt the readers’ side just for empathy. There should be facts and evidence. So, we often reach an agreement with the governmental entity. We have strong ties with governmental entities… [But] if the issue is public, we publish because this is a general issue and there has to be someone who takes action and sometimes [this causes them to] adjust the laws. The government usually responds. I would say more than ninety per cent of cases get resolved… Sometimes our role is like a mediator and sometimes we are social reformers. Sometimes we publish and there is a clash between us and the government. This is the press. We must take action.

The complexity involved in balancing interests reflects the complicated nature of media products as goods, especially news. We return to this in the discussion section when addressing RQ3. Here, we see a operational example of editorial dynamics in a hybrid regime that is not an entirely autocratic system because negotiation affects outcomes.

We found contradiction between journalists seeking greater independence who felt constrained by editors acting on behalf of their organizations and were motivated by political sensitivity to contextual forces in the social system. This complexity was further indicated in journalist experiences collecting information from scientists in universities. Bureaucratic routines serve a gate-keeping function. One journalist said of universities in Qatar, some of which are affiliated with Western institutions, that many times professors and other researchers are reluctant to release information or difficult to contact due to bureaucratic blocks. Speaking of institutions more generally, a journalist explained, “Some are closed and afraid of statements. I mean, sometimes there is a kind of hesitation… There is a blackout on them by the minister’s office or by the state. Or their statements must go through a filter before they can be delivered.” This is another factor explaining the high degree of reported churnalism.

Discussion and Limitations

We analyzed influences affecting the practice of science journalism in Qatar from a perspective centered on managerial and economic aspects. The analysis generated useful answers for the three research questions. Regarding RQ1, we found political and economic influences on editorial decision-making in the production of news about science and journalistic practice generally. This confirms findings of other studies that applied the HoI model which indicate the social system establishes the operational context. Economic influences are linked to the sources and availability of financial resources that have become more scarce in recent years. Resource scarcity was framed as a primary justification for both the coverage and churnalistic routines. Political considerations clearly exert pressure to report on some topics but not others, and on all topics in ways that conform to laws and norms characteristic of the social system that contextualizes journalistic practices. The bureaucratic routine is pertinent here.

Based on our findings, we propose extending the ‘dual market goods’ concept in media economics to multimarket goods. The dual market concept posits that commercially financed media firms must balance satisfying audience and advertiser demands (e.g., Noam 2018; Doyle 2013; Picard 2011). Pertaining to RQ3, the findings support conceptualizing news content as multimarket goods because the balancing work involves authorities as well. Coping with the ‘powers that be’ is a pervasive concern for journalism everywhere. In Qatar and elsewhere in the Global South, it tends to be more transparent than in the West. Our findings suggest the negotiating process is strategic in orientation and animated by interests that correspond in some ways but contradict in others with stakeholders within and across HoI levels.

The dual market concept acknowledges the challenge of balancing interests between audiences and advertisers. For example, while audiences may prefer less ads and can be annoyed by intrusive displays, advertisers pay to be noticed and may prefer limiting the potential to avoid ads. Their interests are contradictory. On the other hand, audiences want to know about new products, features, benefits, and so forth and may value ads for the information value, which corresponds with advertisers’ interests. Adding authorities to the mix similarly indicates corresponding and contradictory interests. Audiences might like to see a more critical orientation in news coverage of politics, for example, although not to an extent or in ways that stir civil unrest, as the literature review suggested regarding how journalists are reportedly viewed in Egypt. In the Qatar context, display ads in newspapers are often about government initiatives, services, or activities. Such sponsored announcements indicate corresponding interests between authorities and news organizations. More can be said, but this is perhaps enough to illustrate the value of extending the dual market goods concept to multimarket goods. The notion needs further development, but holds promise for advancing theory.

Returning to RQ2, we found the Hierarchy of Influences model helpful for understanding the complexity of interdependencies that co-determine the production of news content, particularly science news. We believe consideration of corresponding and contradictory interests enriched analysis of the dynamic interactions of influences within and across the five levels of the HoI model. As an analytical tool, the model affords ample opportunity to study strategic decision-making among editors and journalists, and how decisions are operationalized in professional routines. Our focus on interests at the intersection of motivations and concerns indicates a complex assortment of influences. By emphasizing the reflexive and dynamic character of interacting interests and treating them as over-determinant factors in strategic decision-making, the model has richer relevance for research on media management and economics.

The findings shed light on governing assumptions and considerations of editors and journalists in Qatar regarding how they understand and practice science journalism. Our analysis confirms the understanding that management matters for understanding media conduct and performance (Rohn and Evens 2020). This is evident in editorial decisions that indicate: a) ambivalence keyed to perceptions of low public interest in science, b) low editorial prioritization, c) deciding not to invest in science news production, d) ambivalence about investment in specialized training, e) a focus on balancing the interests of audiences and authorities, and f) churnalism as a characteristic routine.

Of the four decision categories proposed by Taherdoost and Madanchian (2023), our findings suggest that most decisions by the editors we interviewed reflect a combination of constructions and evaluations; constructions because editors decide what to report and how to report it based on considerations of available resources, and evaluations in considerations of how topics should be covered or not in relation to formal and informal requirements based on applicable laws and norms. We found more variation in evaluations between editors, while constructions were generally shared commitments varied across editors, and between editors and journalists.

There are limitations. The interviews were a convenience sample conducted in one country in a period that coincided with the last phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. While our findings about science journalism in Qatar confirm the work others have done on this genre of coverage elsewhere in the Global South, this case and our findings cannot be generalized. We were also unable to interview journalists associated with Doha News, which was regrettably constrained from publishing during the study period. Their coverage of Qatar’s political system has tended to be more critical in tone than the other newspapers. It would be useful to incorporate them in a follow-up. The pandemic context was also an atypical period, albeit one in which news about medical science had heightened importance. Longitudinal research is needed to develop a more comprehensive set of insights and understandings. Our project was the first of its kind in Qatar, which is a unique context.

The novel contributions of our study can be summarized in two aspects. First, our findings encourage a recommendation to extend the dual market goods concept to a multimarket goods concept, a reconceptualization that will augment the traditional emphasis on Audiences and Advertisers by adding the influences of Authorities. Media are social technologies and news production has political aspects and implications. That is true everywhere, even if more transparently evident in a country such as Qatar. While acknowledging important economic influences that are central to the dual market concept in commercially-funded media, there are equally important political influences in all types and structures of media –non-commercial and commercial, public and private. More research is needed to tease out nuances and develop insights about dynamics that characterize interactions in a tripartite structure, and their social/societal implications.

Second, this work highlights the significance of corresponding and contradictory interests as explanatory factors to improve understanding of the range of influences exerted within and between levels of the HoI model. We have approached this by situating the treatment from the perspective of strategic decision-making as an editorial function. We have only taken a first and somewhat tentative step. Further research is needed to expand on this, particularly in relation to journalists, not only editors. While incorporating interests and SDM both need further research, we believe the findings indicate this line of inquiry holds promise for generating insights to enrich understandings of what is and is not produced, and why, from a perspective rooted in the discipline of media management and economics. Moreover, the emphasis on interests was helpful in demonstrating how relations within the organizational level are neither homogeneous nor stable.

More research using the Hierarchy of Influences model in non-Western societies is needed, and our use of the model is an extended version that requires further testing. We believe the study is a useful contribution to both extending the HoI model and applying it to non-Western contexts.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Qatar National Research Foundation for funding the study. Sincere appreciation for the contributions of fellow research team members: Professor Jairo Lugo-Ocando, Dr. Sima Hamedeh (postdoctoral researcher), and the following undergraduate research assistants: Ms. Mariana Xavier Brito de Araujo, Ms. Areesha Khan Lodhi, Mr. Hakem Al Meqdad, Ms. Lena Raed Nawaf Al-Homoud, and Ms. Azma Hasina Mulundika. We thank the NU-Q Research Office for administrative support, especially Dr. Elizabeth Lance and Ms. Bianca Simon. We warmly thank Dr. Everett Dennis, former NU-Q Dean, for his support in the grant and project, and Professor Craig LaMay in the Medill School at Northwestern University for contributing insight on Qatari media law. Most importantly, we especially thank and acknowledge the significant contributions of Professor An Nguyen at Bournemouth University who has been our steadfast, invaluable partner in the research project from inception to conclusion. The authors of this article take full responsibility for all contents.

Note

The research project was funded by the National Priorities Research Program-Standard (NPRP-S) twelfth (12th) Cycle Grant # NPRP12S-0317-190381 awarded by the Qatar National Research Fund (QNRF), a member of Qatar Foundation (QF). The project was titled: Assessing the Qatar News Media’s Capacities for Fostering Public Understanding of and Engagement with Science. The findings reported here reflect the work of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of QNRF or QF.

[1] For an unofficial English translation of the law, see https://www.cra.gov.qa/en/document/cybercrime-prevention-law-no-14-of-2014