The impact of DIF on HEE

DIF, as a product of the digital economy and inclusive finance, is characterized by inclusivity and accessibility (Zhang and Posso, 2019; Yang et al., 2022). It has generated significant positive impacts on residents’ lives (Youxue and Shimei, 2022; Zhang and Posso, 2019; ZHANG et al., 2019). Some scholars have examined the relationship between DIF and education expenditure. As an essential component of household consumption, several studies suggest that DIF influences HEE by altering overall consumption patterns (Li et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2022).

Although the development of DIF may have adverse effects on household decision-making—such as widening disparities among groups, exacerbating the digital divide, or increasing the risk of financial pitfalls (Feng et al., 2024; He and Liu, 2024; Wang et al., 2023)—its overall impact remains largely positive. The inclusive and digital nature of such financial services expands opportunities for households, with more access to investment and more positive channel to income and consumption. Within the framework of behavioral economics(Thaler 1990), consumption is highly sensitive to current income. Changes in income often lead to adjustments in household resource allocation. Households typically maintain a system of mental accounts. When income increases due to unexpected factors, the additional resources are frequently allocated to non-routine expenditures, such as educational spending.

In addition, the digital economy and associated technologies enhance communication tools in public education, thereby improving student learning outcomes (Derksen et al., 2022; Liou et al., 2022). Simultaneously, DIF enhances financial accessibility, facilitating investments in human capital and enabling access to household education loans (Basnet and Donou-Adonsou, 2016; Wei et al., 2021). While these two strands of literature provide valuable insights, they do not fully address the specific impact of DIF on HEE, leaving a critical research gap.

Despite the limited direct evidence regarding DIF’s effect on HEE, this study draws upon the above analysis to propose the following hypothesis:

H1: DIF can significantly influence household education decisions by increasing HEE.

Mechanism of DIF’s impact on HEE

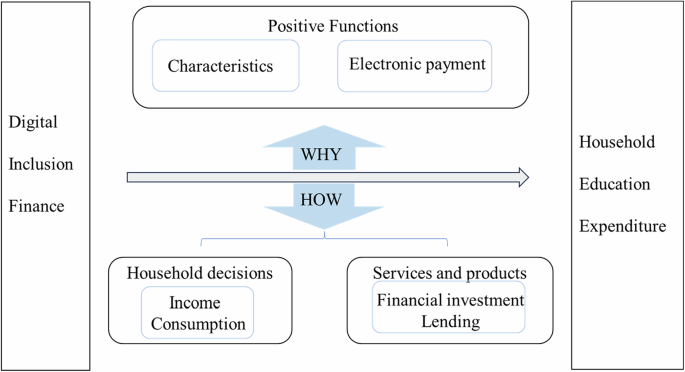

DIF is a comprehensive index with multiple positive functions, comprising three primary dimensions and several sub-indices, including the Payments, Credit, Insurance, and Credit and Money Fund Indices. DIF is measured across three dimensions: depth of use, breadth of coverage, and digitalization, which respectively capture the demand, supply, and convenience of online financial products and services (Guo et al., 2020). The data primarily originate from Alipay users, reflecting real usage patterns and user preferences across different regions, thereby providing valuable insights into regional disparities.

Existing research highlights that the depth of use often amplifies the economic effects of the digital economy. Breadth of coverage, by enhancing access to financial services, facilitates the achievement of inclusive finance goals. Moreover, the convenience and practicality of functions such as digital payments and credit services can directly influence individual decision-making. Zhao and Jiao (2024) demonstrate that differences in the demand and supply of internet financial services are critical mechanisms through which DIF promotes common prosperity. Luo and Chan (2022) identify the utilization of financial services as the most prominent feature of DIF. Similarly, Lai et al. (2022) empirically show that third-party payment platforms, represented by Alipay, play a significant role in alleviating households’ credit constraints, thereby driving up household debt levels. Since HEE reflects family education decision-making and varies with household preferences and attitudes, the diverse positive features of DIF may explain its impact on HEE.

DIF can influence household economic decisions and behavior through multiple channels (Li and Sui, 2023). On the one hand, DIF has created more job opportunities and entrepreneurial prospects(Li and Liu, 2023; Yang et al., 2022), leading to higher income levels for residents (Wang and Fu, 2022). According to the human capital hypothesis, an increase in expected income enhances investments in human capital (Devicienti and Rossi, 2013; Dong et al., 2023). As income rises, low-income households tend to allocate a greater proportion of additional income to education(Chi and Qian, 2016), while subsidies also increase overall HEE (Dong et al., 2023). Since household education decisions are often constrained by income levels (Wang et al., 2024), changes in income can prompt families to adjust their educational choices, thereby affecting HEE. On the other hand, DIF has expanded consumer groups by facilitating online shopping (Li et al., 2020). Online transactions reduce time and transaction costs for businesses, thereby promoting consumption upgrades (Zhou, 2024; Zhou et al., 2023). For households, this reduction in consumption costs indirectly relaxes income constraints, leading to increased attention to education and changes in HEE(Liu and Morgan, 2016).

DIF also provides convenient financial products and services (Du et al., 2023). The diversity of online financial products stimulates residents’ investment interests, thereby influencing traditional financial investment patterns (Lu et al., 2023). Financial investments, in turn, affect household decisions regarding education-related savings (Chein and Pinto, 2018; Gu and Arends-Kuenning, 2022). From a life-cycle perspective, individuals adjust their consumption and saving behaviors in response to evolving needs across different stages of life. For example, young adults may engage in consumption smoothing through borrowing. Middle-aged individuals are more likely to prioritize precautionary savings. In contrast, the elderly tend to rely primarily on consumption. This behavioral pattern also applies to households at different stages of the family life cycle. When Chinese households have children attending school, HEE becomes a major component of expenditure. In such cases, if households have access to additional income or possess a stronger capacity to bear risk, parents may adjust their financial decisions accordingly. Specifically, they may increase spending on human capital investment by allocating more resources to HEE.

For families that have not yet made financial investments, DIF offers predictable returns, which can alter their education decisions and increase HEE. Furthermore, DIF’s credit payment features complement traditional financial services by lowering barriers to conventional financial lending (Hu et al., 2023; Lu et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023). This strengthens the vitality of the credit market (Yue et al., 2022) and enhances households’ risk management capabilities (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2021) thereby reducing the need for precautionary savings. For households that have not yet engaged in borrowing, DIF relaxes borrowing constraints and improves risk resilience, ultimately leading to increased HEE (Banerjee, 2004; Huang et al., 2010; Wei et al., 2021).

Based on this analysis, we propose the following hypotheses regarding the mechanisms through which DIF affects HEE, and Fig. 2 is used to visually demonstrate these mechanisms:

H2: The breadth of coverage, depth of use, and degree of digitalization in DIF result in changing of impact on HEE, with mobile payment functions playing a critical role.

H3: DIF, by increasing expected income and reducing consumption costs, encourages households to adjust their education decisions, thereby increasing HEE.

H4: The financial products and services enabled by DIF alleviate household credit constraints and enhance risk management capabilities, leading to increased HEE through greater human capital investment.

Heterogeneity of the impact

The impact of DIF on HEE is influenced by urban development levels, household characteristics, and educational demand factors. The development of DIF relies heavily on digital infrastructure (Feng et al., 2024). On the one hand, geographic factors (Yang et al., 2022), industrial structures, and urban-rural disparities (He and Liu, 2024) create regional heterogeneity in DIF. As a result, city development becomes a critical factor when analyzing differences in the effects of DIF (Li et al., 2020; Zhou, 2024). On the other hand, residents’ digital literacy and human capital levels significantly affect their ability to utilize DIF, leading to heterogeneous impacts across households. Factors such as educational attainment (Feng et al., 2024; Li et al., 2020) also influence household education decisions (Qian and Smyth, 2011).

Educational decisions are closely aligned with changing educational needs(Qian and Smyth, 2011), which tend to evolve with age, leading to corresponding shifts in HEE. Household education decisions often vary based on the types and needs of children. During a child’s developmental stages, parents adjust their human capital investments accordingly. For instance, younger children, who are more receptive to new knowledge, are often the primary recipients of extracurricular training. Gender differences also play a role in educational decision-making(Kenayathulla, 2016), with families often selecting educational paths aimed at nurturing specific traits or skills. When income constraints are stronger, age and gender become more pronounced factors influencing the allocation of household education investments.

HEE can be broadly categorized into in-school and off-campus expenses. In-school expenses encompass fees charged by schools, including costs for meals, accommodation, books, and equipment. In contrast, off-campus expenses primarily include extracurricular tutoring and expenditures on educational software and hardware. Households generally have greater decision-making autonomy over off-campus expenditures. Luo and Chan (2022) highlight the multifaceted role of shadow education across different levels of the educational ecosystem. Chi and Qian (2016) find that while increased compulsory education expenditure effectively curtails in-school education costs, out-of-school expenditures significantly contribute to rising HEE. Similarly, Di Gioacchino et al. (2019) demonstrate that when access to higher education is restricted due to low inclusion, the share of public expenditure on higher education tends to increase. However, in such cases, low-income groups are less likely to support public spending on education.

In the Chinese education system, family educational decisions play a more critical role before the university stage, especially during key transitional periods such as high school. The highly competitive Gaokao system intensifies educational competition. To secure better educational opportunities, students in high school often experience heightened academic pressure. Moreover, younger students (before high school) tend to have more time and energy to engage in diverse after-school activities, which further contributes to higher HEE (Song and Zhou, 2019).

Given these differences, it is essential to explore whether DIF affects HEE differently across various conditions. Disparity of cities, family circumstances, and educational needs may affect education decisions. Additionally, cost types and the pressure of exams are also closely related to household education choices. The results could provide empirical evidence to promote educational equity and reduce gaps in educational investment.

Based on this analysis, we propose the following hypotheses:

H4: The impact of DIF on HEE varies with differences in regional development, household human capital levels and the educational demand of children.

H5: The impact of DIF on HEE is heterogeneous due to varying educational demands and pressures.