My Neighborhood News Group (MNNG) is publishing a series of stories on how local governments are funded and the financial challenges facing both elected officials and residents. You can read Part 1: Introduction here. Part 2: Where’s the money here. Part 3: Property taxes here. Part 4: Fees and taxes here. Part 5: Federal and state grants here.

Local governments say they need to fund “core services,” a term often used during a funding crunch.

Core government services are generally accepted as services vital to a community’s safety, health and infrastructure. They are the foundational functions that residents expect their government to prioritize.

Common examples include law enforcement, fire protection, emergency medical services (EMS), road maintenance, traffic management and election administration.

In urban areas, core services may also include utilities like water and sewer management, garbage collection and measures to address frequent natural disasters, such as flood control.

While the state mandates that local governments provide certain services, local governments (with input from the community) determine the what and how much of local services because they are what the public cares about and wants the most.

But who decides what those top priorities are?

“The areas we have more flexibility in cutting are ones that the public rightfully expects and demands from their county government,” Snohomish County spokesperson Kari Bray said.

Bray described these areas as “things like public safety, parks and conservation of our natural spaces, planning for the future growth and economic vitality of our county, emergency readiness and response, preventing or responding to health hazards, or facilitating support for families, seniors, veterans, and more.”

These functional “nice-to-haves” sometimes end up as special taxes or levies that go before voters to approve. They are usually minimal in cost – like 0.1% in additional property or sales tax. Voters say yes, sometimes. Other times, they say no.

For example, voters did not pass the public safety sales tax that appeared on the Snohomish County ballot in November 2024. That would have generated an estimated $23.8 million for the County’s portion of the tax (another $15.8 million would have been split among the cities).

Local governments pick up the tab for state requirements.

Like most states, Washington has statewide mandates. Mandates are regulations, rules or requirements local governments must follow and pay for through property taxes or other financial solutions.

Statewide mandates exist to establish uniform standards across a state, address regional issues, and compel local governments or individuals to act in ways that serve broader public interest. State legislatures and agencies use them to set minimum levels of service, manage resources and address significant crises.

Mandates come from court rulings, policy priorities or citizen initiatives. They become state regulation or law.

Local governments and residents have both expressed frustration with state mandates. Local governments believe they should have autonomy over things like building codes and environmental rules. Local governments do have some autonomy, but not as much as they’d like.

Some examples of state requirements

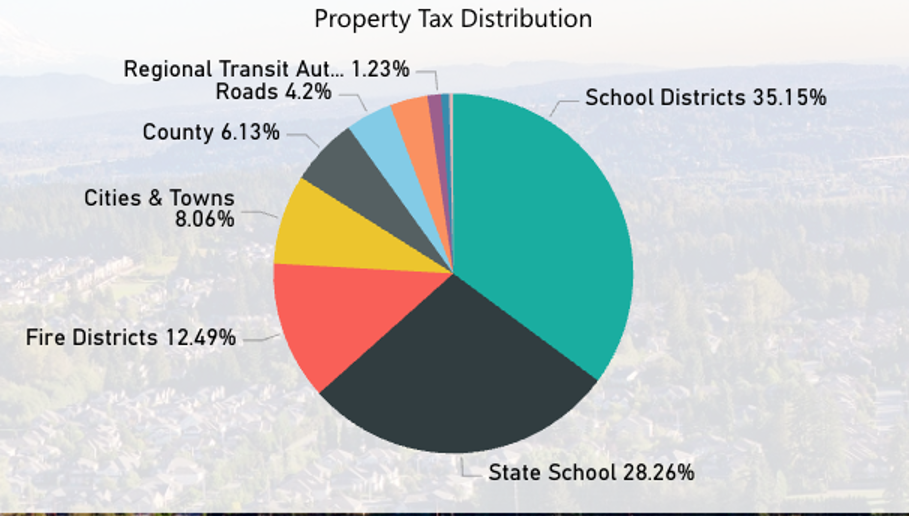

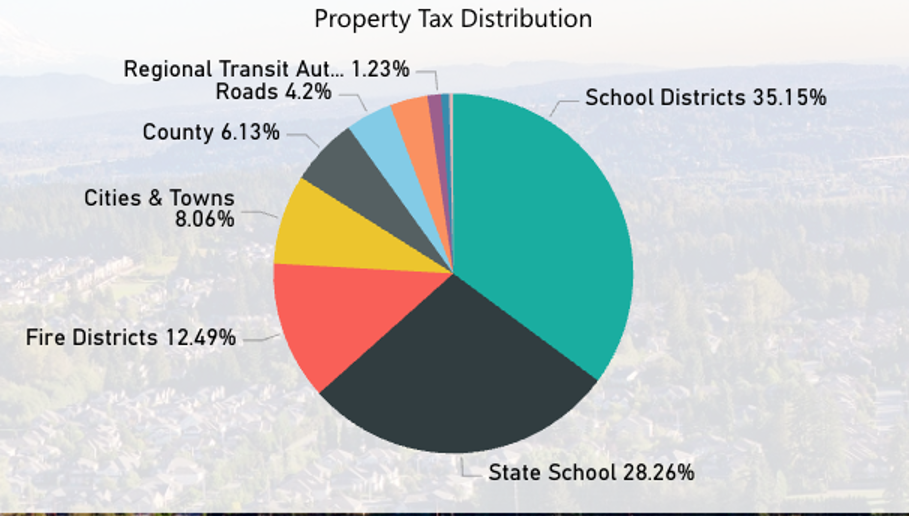

Local property taxes fund K-12 education statewide to even out inherently unequal funding between wealthy and poor school districts. That slice of the property tax pie is called “State School.”

Local districts can add to that with local levies, which Edmonds School District voters do. That slice of pie is called “School Districts.”

Public requests lead to state guidelines and mandates

The public has the right to government documents through public records requests. A legislative audit surveyed 230 Washington state public agencies and learned agencies received nearly 438,000 public records requests in 2023, with most requests coming from individuals, insurance companies and law firms. That number was up by more than 100,000 in three years. Responses increased from 15 days to 25 days and longer, depending on the request.

Recently, State Attorney General Nick Brown proposed new guidance for local governments to compel them to do that work faster.

What happens when the number of people to fulfill those timely requests are cut? What is the value to the community? More importantly, where does the money come from to do that work? Does it get dropped? Delayed? Is the local government now out of compliance with the State Public Records Act?

Local governments must figure out how to address these mandates. Some recent examples include:

Building project reviews: SB 5290, the Local Project Review Act approved in 2023, speeds up the permitting processes for residential housing and developers with new tighter deadlines. If a local government permit is not reviewed within the timeline, fees are refunded. Many permitting offices are self-funded.

This seems like a good idea. However, with fewer reviewers (the result of budget cuts), local governments may not meet their deadlines and may end up refunding more money than expected. But this speedy review generates permitting and property tax dollars more quickly. Is it too quick? What if something is missed? It’s a new mandate that must be managed.

Indigent defense caseload

In June 2025, the State Supreme Court called for changes to indigent defense caseload standards, mandating a lowered number of cases that constitutionally required public defenders can take in Washington.

“This means that cities will need to hire more public defenders to cover the existing caseload,” Association of Washington Cities spokesperson Brian Parry said. “Cities are already struggling to hire enough public defenders under current conditions because of limited funding and the basic fact that there aren’t enough public defenders available for hire in the first place.”

“Without options to pay for or hire more public defenders, cities may have no choice but to drop or dismiss cases,” Parry added. Fifteen cities in an AWC survey said they were forced to dismiss cases because they could not provide a public defender.

For Edmonds, that public defender cost increased $353,000 in one year.

For Mountlake Terrace, it cost $220,000 for public defense in 2025 and $480,000 in 2026.

“We were told that even if you took all the students in law school right now and made them public defenders, it still wouldn’t be enough to manage the existing backlog of cases,” said Mountlake Terrace City Manager Jeff Niten.

State Sen. Jesse Saloman (D-Shoreline) explained this problem to the Mountlake Terrace Council in mid-December.

This particular mandate is frustrating to many. No one wants cases dismissed, especially if you are the victim of that crime.

But the U.S. Constitution’s Sixth Amendment includes the right to legal counsel. That’s what this mandate promises. It will be expensive, and cases may take longer to move through the justice system.

Some people say, “If it’s not funded by the state, then they shouldn’t force us to do it!” Fair statement. But that’s not where we are.

Other state mandates look very different. Take, for example, clean water. The Washington State Department of Ecology requires cities to clear every single city storm drain every two years. That work is done by a vactor truck, a $600,000 piece of machinery, owned and maintained by the city with skilled operators and many storm drains.

That is a mandate, a condition the local governments must meet to stay in compliance with the state.

Going back to our personal economy analogy: Imagine you buy a house in a community. You live there a few years and you can afford it. The community then votes to create an HOA. You didn’t vote for the HOA but the HOA happens anyway. The HOA now says you must pay an extra $300 a month for gardeners, new signs and trash can enforcement. You can’t afford that. But it doesn’t change the fact that you have to pay… or they will fine you or place a lien on your home.

“You can always move.” Isn’t that what we hear? But people can’t – they don’t want to or they literally can’t afford to. They are stuck. And mad. Can you blame them? This is an unfunded mandate that you (and maybe your local government) doesn’t like.

Next: The color of money and the new (and expensive) challenge to local government finances.