There’s something profoundly strange happening in fashion right now. Walk into any luxury boutique and you’ll find $890 hoodies that look like they were stolen from a skate park. Flip through any runway lookbook and the silhouettes (baggy, layered, purposefully disheveled) echo what skaters have worn for decades. The irony is thick: a culture built on rejecting mainstream approval has become mainstream’s most coveted reference point.

What makes skater fashion even more fascinating, though, is that it couldn’t care less about mainstream trends.

The culture that refuses to pivot

When entering the spotlight, most fashion movements bend. Normally, that bending is precisely why they are able to infiltrate the masses. But skater fashion is not normal. It’s the same torn jean and scuffed Vans it was forty years ago, the same oversized graphic tee, loose shirt, worn hoodie, and slouched posture. Skater style remains stubbornly, defiantly, itself.

This is because skater fashion’s consistency is not random. It comes from utility. When skaters in 1970s California chose loose-fitting clothes and slip-resistant sneakers, they were choosing what worked for the physical demands of skating. The logic holds today. Baggy jeans aren’t trending because they’re retro; they’re present because of comfort: tight pants restrict movement when you’re attempting a right stick up ollie. Volume in clothing is a functional requirement that happened to look really nice.

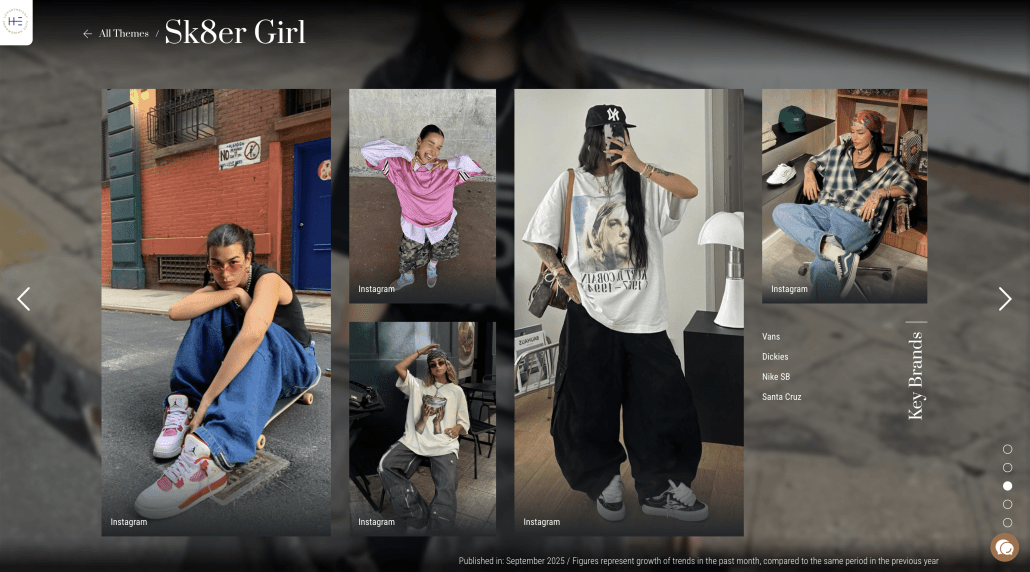

Image: Data from Heuritech Market Insights Platform

The anti-authority becomes authority

Thrasher Magazine understood this from day one. Founded in 1981 by Eric Swenson and Fausto Vitello, initially as a vehicle to promote their truck company, the magazine became an underground, raw alternative to publications promoting skating as a polished mainstream activity. While other skateboarding media tried to make the sport palatable, Thrasher leaned into its grit. Their motto, “Skate and Destroy”, wasn’t marketing speak. It was a worldview.

What Thrasher captured better than anyone was the visual language of skateboarding. Raw photography, brutal falls, concrete and coping and blood. Each issue acted like a time capsule, revealing how different regions contributed to the larger narrative of skateboarding. The magazine didn’t just document skate culture; it codified its aesthetic vocabulary, what looked real, what felt earned, what counted as authentic.

The Thrasher flame logo tells you everything you need to know about the relationship between skate culture and mainstream fashion. Even in the 1990s, musicians like the Beastie Boys and Sonic Youth wore Thrasher clothing as part of the punk and hardcore culture. But by the 2010s, that logo was appearing in contexts that would have been unthinkable a decade earlier, on Rihanna, on runways, in Vogue editorials.

That’s the tension at the heart of skater fashion: it became culturally dominant without seeking cultural dominance, and when the mainstream came calling, it refused to play along.

The style that won’t style itself

The current moment in skater fashion is marked by a strange kind of victory. In 2026, technical fabrics with enhanced stretch and water resistance will keep being incorporated into skate bottoms while maintaining classic silhouettes. Heritage footwear is resurging, Vans Knu Skool saw an 83% increase, Adidas Campus continues steady growth at 16%. Baggy jeans are up 15%. But these aren’t trends in the traditional sense. They’re not seasonal or cyclical. They’re the market finally catching up to what skaters have known all along: this is what works.

What’s remarkable is how resistant skater fashion remains to its own success. Pro skaters and industry observers note that skaters are increasingly being influenced by other cultures rather than the other way around, soccer jerseys, Merrells, influences from outside traditional skate brands. Rather than seeing this as dilution, the culture absorbs these elements and moves on. There’s no branding committee deciding what’s “on brand.” There’s just what people actually wear when they skate.

This creates a fascinating dynamic with luxury fashion. Louis Vuitton’s Virgil Abloh signed Palace skateboarder Lucien Clarke as the first-ever LV-sponsored skater, a move that should have been a watershed moment. Gucci, Celine, Valentino, they’ve all released skate-inspired pieces and capsule collections, often at high price points that would fund a year’s worth of actual skate gear, key examples of how rebellion gets repackaged for sale. What began in skateparks as utilitarian need has grown into a fashion revolution, with luxury brands rushing to tap into the raw, rebellious energy of skateboarding style. But authenticity cannot be imitated.

And here’s the thing: they’re right. You can manufacture the look, the oversized fit, the weathered aesthetic, the graphic language, but you can’t manufacture the wear patterns that come from actual use. You can’t design the scuff marks that accumulate from hours spent pushing concrete. The difference between a $900 designer skate shoe and a $70 pair of authentically thrashed Vans is provenance.

Image: Data from Heuritech Market Insights Platform

The demographics that don’t matter

One of the more interesting aspects of contemporary skater fashion is how little it cares about traditional fashion demographics. Skaters don’t dress to impress, they dress to move, creating a raw, fluid, and intentionally unpolished aesthetic. There’s no gendered marketing, no men’s versus women’s positioning, no age segmentation, no reliance on teams, leagues, or the conventions of organized sport. A 15-year-old and a 45-year-old can wear identical outfits and neither looks out of place because the clothes aren’t about signaling who you are, they’re about facilitating what you do.

This creates problems for brands trying to commodify skate style. Traditional fashion operates on newness, on seasonal refreshes and trend cycles. Skater fashion operates on the opposite principle: if it works, don’t change it. Dickies work pants have looked essentially the same for decades. Vans Old Skools are Old Skools. The Supreme box logo hasn’t evolved because it doesn’t need to evolve.

Even as sustainability becomes a talking point in skate fashion, with brands incorporating recycled materials and eco-conscious production, the fundamental approach remains unchanged: make durable clothes that last. The sustainability isn’t a marketing angle, it’s a byproduct of making things that hold up over time.

The counterculture becomes culture

Skateboarding emerged from underground rebellion to become a global force, born in gritty 1970s California streets. What’s changed isn’t the fashion itself but the world’s relationship to it. Where skate style was once marginal, it’s now central. Where it was once dismissed as juvenile or delinquent, it’s now studied and emulated by the highest echelons of fashion.

Yet the culture hasn’t adjusted its posture. When skateboarding was added to the Olympics, Thrasher made clear it refused to cover the sport in that context. Their reasoning was simple: they didn’t need to make the Olympics cool. This stance, rejecting mainstream legitimacy on principle, is what keeps skate culture’s fashion authentic.

The brands that remain respected within skating are those that never tried to transcend it. Vans, Nike SB, Dickies, Santa Cruz are brands whose logos function more like earned badges than fashion statements. Even legacy names like Powell Peralta remain respected because they never abandoned skating itself. They’re not aspiring to be something other than what they are. They’re not positioning themselves as lifestyle brands or chasing runway credibility. They make clothes and shoes for people who skateboard, and if non-skaters want to wear them, that’s incidental.

Image: Data from Heuritech Market Insights Platform

What’s next

The question hovering over skater fashion in 2026 isn’t whether it will remain relevant, it clearly will. The question is whether it can maintain its authenticity as its influence grows. And the answer, based on its history, is probably yes, but only because it refuses to care about the question.

Skater fashion endures precisely because it’s not trying to endure. It’s not optimizing for longevity or planning for the next wave. It’s just existing in its own space, wearing what works, moving how it moves, completely indifferent to whether anyone is watching.

That indifference is its superpower. In an era where everything is performed for an audience, where every aesthetic choice is a personal brand statement, skater fashion remains resolutely unpretentious. It’s not trying to look cool, it just happens to be cool because it’s too busy doing something else to worry about how it looks doing it.

The mainstream can borrow the silhouettes, replicate the graphics, and study the attitude. But it can’t manufacture the one thing that makes skater fashion compelling: the fact that it genuinely doesn’t care whether you get it or not. It’s fashion for people who wear clothes, not people who curate them. And in 2026, when everything is content and everyone is their own media brand, that might be the most radical stance of all. Skater fashion isn’t trying to teach you anything. It’s too busy moving forward on its own terms.