When comet 3I/ATLAS was discovered in July 2025, on a one-way interstellar journey through our Solar System, Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb suggested it might be an alien spacecraft paying us a visit.

Back in 2017, he made similar claims about the very first known interstellar object, the asteroid 1I/‘Oumuamua.

In fact, despite their somewhat unusual properties, both celestial bodies appear to be completely natural, and most astronomers dismiss Loeb’s speculative assertions.

But what if he was right? What if we really did find a piece of alien hardware?

“Proof of the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence would be the most important discovery in human history,” says Andrew Siemion, principal investigator at the privately funded Breakthrough Listen programme.

And while Breakthrough Listen uses radio telescopes around the world to search for possible interstellar broadcasts – an approach known as SETI (Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence) – astronomers are now thinking seriously about how to broaden the search by looking for ‘technosignatures’, other telltale traces of alien technology.

Spaceships, for instance.

The idea isn’t new. In his 1973 science-fiction novel Rendezvous with Rama, Arthur C Clarke described the discovery and subsequent exploration of a huge alien craft that happened to pass through our Solar System.

Five years earlier, in 2001: A Space Odyssey, Clarke and director Stanley Kubrick imagined how mysterious beings left huge monoliths behind in the Solar System to guide the slow progress of human evolution.

What alien tech might look like

SETI pioneer Jill Tarter coined the term ‘technosignatures’ in 2007 to emphasise that there are multiple ways to search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

But while many people believe that UFOs (unidentified flying objects) and UAPs (unidentified aerial phenomena) are proof of alien visits, no one has ever come up with undisputed evidence that ET has rung our doorbell.

Then again, evidence of alien technology might also be found in the distant Universe, and not just in the form of artificial radio messages.

In fact, any weird, inexplicable astronomical observation could potentially hint at the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence (though most astronomers like to warn: “It’s never aliens”).

Jason Wright of Pennsylvania State University, for one, likes to keep an open mind. “Is it likely that we will ever discover technosignatures?”, he asks.

“I don’t know, but I enjoy exploring the idea.”

Searching for technosignatures

In 1959, physicists Giuseppe Cocconi and Philip Morrison first suggested that radio telescopes could be used to eavesdrop on alien communications.

At the time, no one had a clear idea of how likely extraterrestrial life, let alone extraterrestrial intelligence, might be.

Today, things look very different. We now know that planets – including temperate, water-bearing worlds like Earth – are plentiful, and that the carbon-based building blocks of life are all over the place in the Universe.

It seems incredibly unlikely that life has only emerged once.

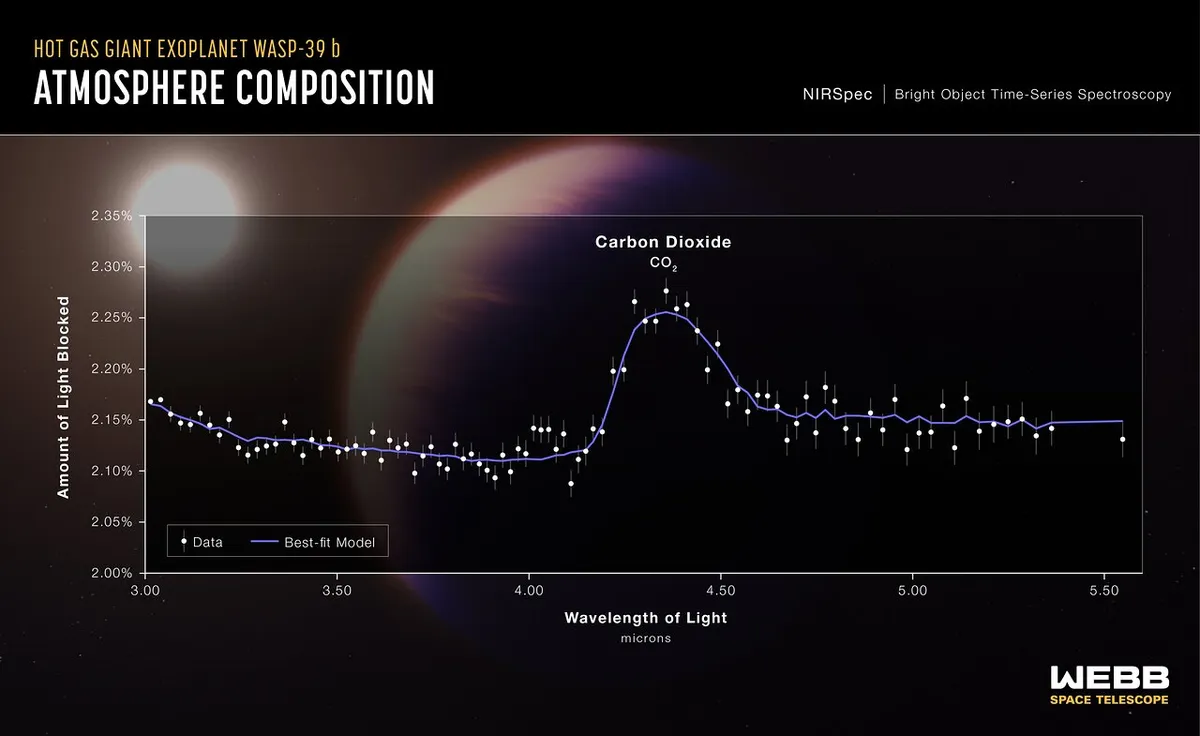

Using sensitive instruments such as the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers are now able to sniff out the atmospheres of nearby exoplanets in the hope of finding so-called biosignatures – molecules that hint at biological activity on an alien planet’s surface.

So far, no convincing detections have been reported, although a team led by Cambridge astrophysicists has claimed the detection of dimethyl sulphide in the atmosphere of planet K2-18b.

The discovery of biosignatures may have to wait for future facilities like the European Extremely Large Telescope or NASA’s proposed Habitable Worlds Observatory.

If biosignatures are already so hard to find, you might expect the search for technosignatures to be even harder.

After all, biosignatures are produced by each and every form of life – even single-celled organisms – while technosignatures require the emergence of intelligence and technology.

But in a 2022 paper, Wright and his colleagues argued that technosignatures (including radio transmissions) might actually be easier to detect.

How technosignatures give themselves away

For one thing, technosignatures could be more abundant, as one single technologically advanced civilisation might spread across multiple planets or even planetary systems.

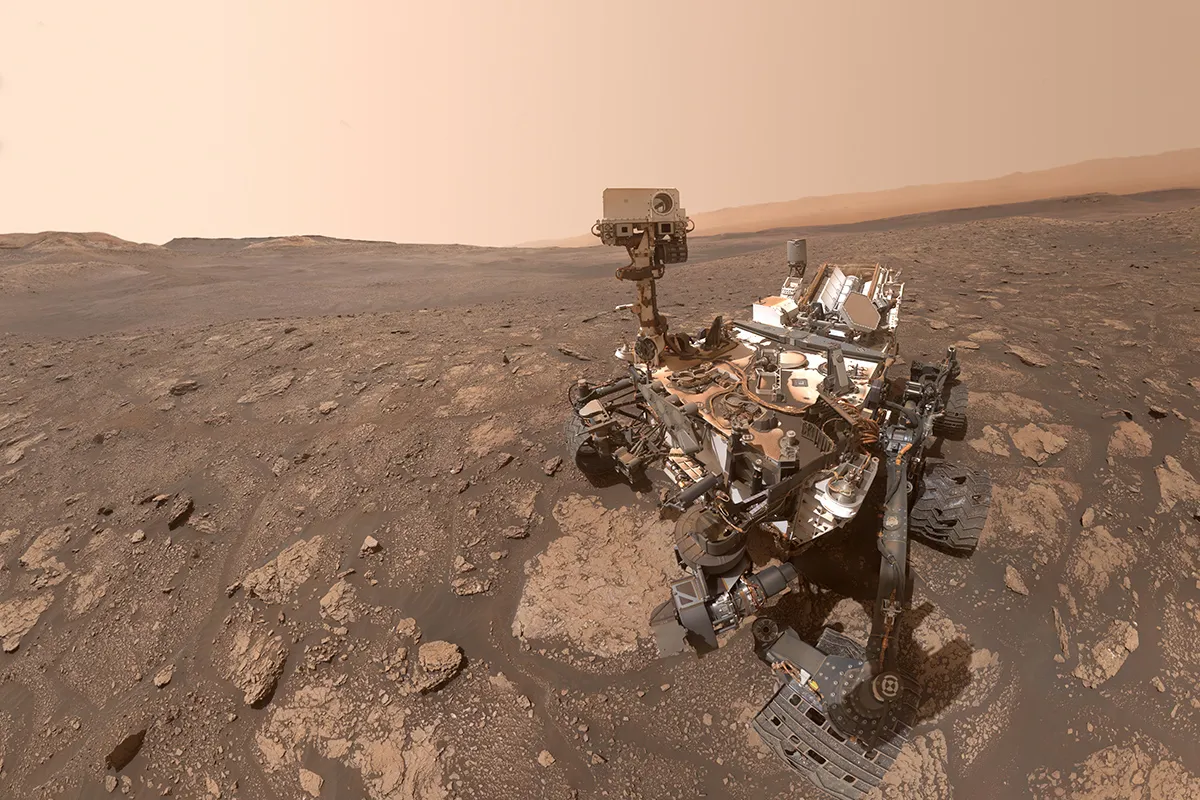

Humanity itself is a case in point, albeit at a modest level: while our biosignatures can only be found on Earth, our hardware is scattered throughout the Solar System – and even beyond.

Moreover, artificial structures could outlive their makers.

Even if the intelligent aliens become extinct, their environmental impact, buildings, machines or self-replicating robots could remain detectable for a very long time.

For example, the Voyager space probes will still peacefully roam the Milky Way long after the Sun and Earth have gone.

Technosignatures – in particular, radio signals – can also be detected over much larger distances than biosignatures, which can only be found (if at all) within a few tens of lightyears.

And finally, according to Wright and his co-authors, technosignatures are much less ambiguous.

While molecules like oxygen, ozone, methane and even dimethyl sulphide can also be produced by non-biological processes (at least in principle), the discovery of a black monolith on the Moon, or a radio signal containing the first million decimals of pi, would be definitive proof of extraterrestrial intelligence.

The Dyson sphere

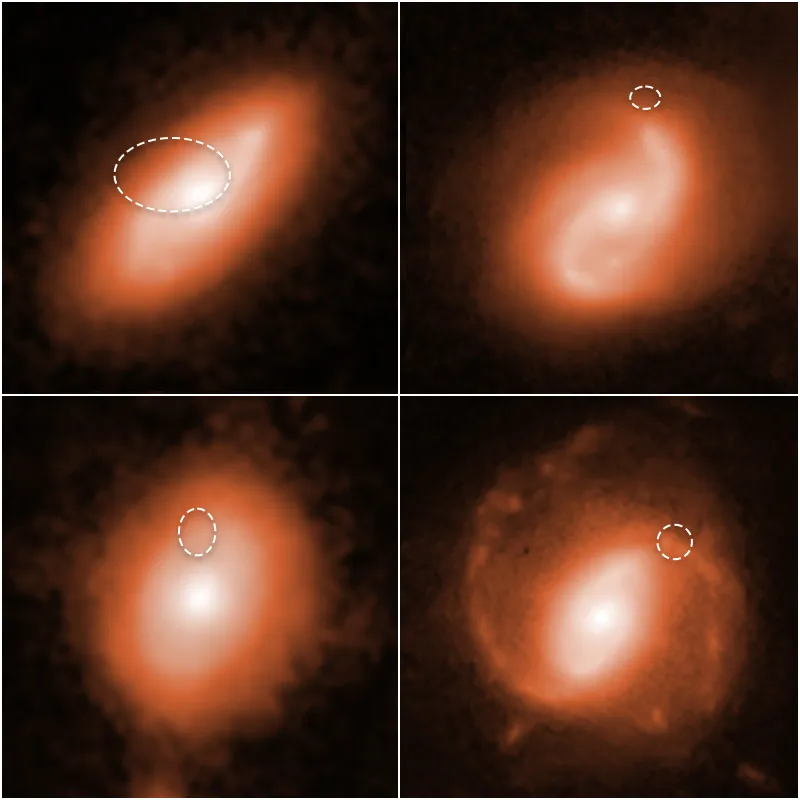

One particular type of potential technosignature (other than alien radio transmissions) was described by visionary Princeton physicist Freeman Dyson back in 1960, just one year after the landmark paper by Cocconi and Morrison.

Long before infrared astronomy seriously took off, Dyson suggested searching for weird infrared stars.

These, he argued, could be huge artificial spheres, constructed by a highly advanced civilisation around their parent star, to collect as much energy as possible.

Physics dictates that the outer surface of such a sphere would emit infrared radiation.

The idea was first proposed by science-fiction writer Olaf Stapledon in his 1937 novel Star Maker, although the concept has subsequently become known as a Dyson sphere.

According to Wright, it’s not very far-fetched. “Collecting energy is probably a fundamental and universal trait of intelligent civilisations,” he says.

Perhaps you don’t need a complete sphere, but even a huge ring of energy-collecting solar panels would be detectable through its heat radiation, or because it might block some of its star’s light.

Tabby’s star

In fact, when Tabetha Boyajian of Louisiana State University announced the discovery of the weird, irregular fluctuations in the light of ‘Tabby’s Star’ – the star KIC 8462852 – back in 2016, some researchers (including Wright) suggested that it might be surrounded by a partly completed Dyson sphere.

Similar suggestions have been made for other stars with hard-to-explain brightness variations or with larger-than-expected infrared excesses.

Although the behaviour of Tabby’s Star still isn’t fully understood, most now believe the brightness fluctuations are caused by an orbiting swarm of giant comets or the debris of a disrupted asteroid.

Apparently, technosignatures are not so unambiguous after all.

But Dyson spheres and other potential alien megastructures, as they are collectively called, are still very much on the radar of SETI researchers.

Keeping an open mind

Obviously, it’s hard to carry out a dedicated search for technosignatures as we don’t know what we’re looking for.

But according to Siemion, any anomalous astronomical object deserves special attention, as it might be our first encounter with alien technology.

For instance, when the first pulsar was discovered in 1967, it received the code name LGM-1, for Little Green Men.

Only later did it became clear that pulsars are rapidly rotating neutron stars.

Fast radio bursts, first discovered in 2007, have also been assigned to aliens, by (who else?) Avi Loeb.

“I won’t exclude that we will find advanced life before we find micro-organisms,” says Siemion.

Even the search for biosignatures could possibly lead to the detection of a technosignature, in the form of chemical pollution of an exoplanet’s atmosphere by large-scale industrial activity on the surface.

Keeping ET in the back of your head is good for science too, according to a 2023 online paper by astronomers Beatrice Villarroel and Geoffrey Marcy.

“Many scientists quote the loss of ‘credibility’ of a certain field – either among peers or funding agencies – when big claims of alien life are made to the media,” they write.

“On the other hand, research activity is often stimulated by the possibility of discovering alien life, regardless of the outcome.”

The future of technosignatures hunting

Wright admits that the chance of success in the search for technosignatures strongly depends on how often life will result in technology – something we simply don’t know.

At the 2024 Life in the Universe symposium in Cape Town, South Africa, eminent paleoanthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie of the Institute of Human Origins in Arizona was sceptical.

“If we ever find extraterrestrial life, it won’t resemble homo sapiens in any way,” he said.

South African archeologist Sarah Wurz voiced a similar concern.

“Our present-day technological capabilities are the result of countless evolutionary coincidences and accidents in the past,” she told her audience.

Siemion, who co-organised the symposium, realises that anthropocentrism is a real problem in our thinking about SETI and extraterrestrial technology.

“Maybe we’re indeed on a completely wrong track,” he said, staring at his eye-catching, alien-green shoe laces, “and there’s no guarantee that we will ever find extraterrestrial intelligence. But, of course, that doesn’t mean we’re giving up.”

As for visiting alien spacecraft: even though there’s no evidence that the first three interstellar objects to visit the Solar System are anything but natural bodies, the next one could be artificial.

That’s why an international group of astronomers, led by James Davenport of the University of Washington and including Jason Wright, Andrew Siemion and The Sky at Night’s own Chris Lintott, published a paper on how to look for telltale anomalies in the shape, colour and trajectory of the many interstellar objects that are expected to be found by the new Vera C Rubin Observatory in Chile.

Who knows, even comet 3I/ATLAS could be a hollow body harbouring an alien habitat.

“The presence of ‘normal’ behaviour, such as natural cometary activity, or surface colours consistent with bare asteroids, should not deter our follow-up observations aimed at constraining technosignatures,” the authors write.

“As with all technosignature searches, if we only look once, we may simply miss an incredibly obvious transmission or signal.”

This article appeared in the November 2025 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine