Two things are true at once — First, humans influence the climate system, presenting risks that merit policy attention. Second, climate research, broadly construed, is a deeply politicized endeavor, leaving much room for improvement.

Of feature of the deep politicization of climate is that some people wish to only believe one of these two truths. Developing effective policies related to energy, development, extreme events and disasters depends upon grappling effectively with these two truths.

In 2024, I created a table of the top five climate science scandals in an effort to shine a bright light on areas where the climate community could readily address some of the most egregious failures within the field.

The scientific community can only control what it can control — Big P politics is not among those things, and there is no guarantee that efforts to uphold scientific integrity will make much difference in the political world. But it does seem clear that securing the confidence and trust of our fellow citizens and those empowered to lead will be much more likely if we act to uphold scientific integrity, rather than letting bad science stand.

In today’s post, I both identify fives scandal that I judge to be the most significant as 2025 comes to a close and recommend positive steps that the community might take to correct course.

With the throat clearing out of the way, let’s get to it . . .

5️⃣ An Undeniably Fake Dataset Used in Research and Promoted in Assessments

In any area of scientific publishing, you will not find a more open and shut case for the retraction of published studies than with those peer-reviewed papers that have used the so-called “ICAT dataset” of economic losses from hurricanes.

As I have documented in detail at THB (here, here, and here) and also in the peer-reviewed literature, the dataset is fake and should have no role in research.

Pielke Jr, R. (2025). Do not use the ICAT hurricane loss “dataset”: An opportunity for course correction in climate science. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 64(4), 401-407.

There are perhaps a dozen or more peer-reviewed papers that employ the fake dataset. One of these papers in particular has been promoted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the U.S. National Climate Assessment (USNCA) to call into question studies that use robust data, and remarkably, physical metrics of hurricanes, such as frequency and intensity.

Recommended actions: Journals that have published these papers should set up a small, ad hoc committee to quickly document the misuse of an Excel spreadsheet found online — This could be done in several weeks, the issues here are neither complicated nor out of sight. Papers that used the fake dataset should be retracted. The IPCC and USNCA should issue corrections. None of this should be difficult, it would be science working as it should and showing the world that when mistakes are made, science self-corrects because that is how science progresses towards truths and earns trust.

4️⃣ The U.S. National Climate Assessment

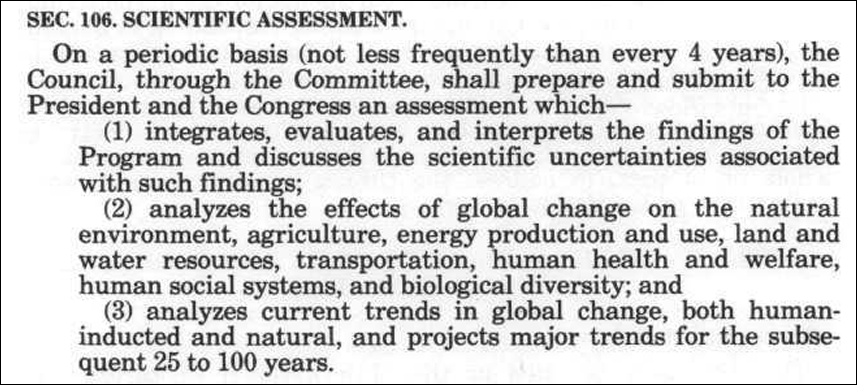

The U.S. National Climate Assessment (USNCA) was established in a 1990 law (that, as chance would have it, was the central focus of my 1994 PhD dissertation). The entire text of the relevant section of that law to the USNCA is shown below.

It would be easy to miss, but there is a design flaw in the directive that has plagued the USNCA over the 35+ years since the law was passed. The “Council” and “Committee” referred to in the legislation are bodies established within the Executive Office of the President — that is, the White House.

That means that the USNCA has always been under the political control of whichever administration happened to be in charge. As climate change became increasingly politicized, the USNCA has proven to be too tempting a target for political meddling — and both Democratic and Republican administrations have used the assessment to advance their political goals, rather than produce a balanced assessment of the state of scientific understandings.

Below, for instance, are just some of the organizations tapped by the Biden Administration to write the fifth USNCA.

Not to be outdone, recent media reports suggest that the Trump administration is going to install its preferred leadership for the sixth USNCA. The pendulum swings.

The problems with the USNCA are bipartisan and extend well beyond Washington — Many in the media and scientific community welcome (and participate in) the politicization of the NCA when done by Democrats but oppose it when done by Republicans.

Recommended actions: Leaders in the scientific community (e.g., NASEM, journal editors, public intellectuals, etc.) should call for a depoliticized USNCA and recommend institutional reforms to make the process more balanced and further removed from political oversight. Congress could (in theory) play an important role here by amending PL 1010-606 to require an institutional structure further removed from White House control.

For further reading:

- Pielke, R. A. (1995). Usable information for policy: an appraisal of the US Global Change Research Program. Policy Sciences, 28(1), 39-77. (PDF)

- Pielke Jr, R. A. (2000). Policy history of the US global change research program: Part I. Administrative development. Global Environmental Change, 10(1), 9-25. (PDF)

- Pielke Jr, R. A. (2000). Policy history of the US global change research program: Part II. Legislative process. Global environmental change, 10(2), 133-144. (PDF)

- Pielke, R., & Sarewitz, D. (2002). Wanted: scientific leadership on climate. Issues in Science and Technology, 19(2), 27-30.

- Sarewitz, D., & Pielke Jr, R. A. (2007). The neglected heart of science policy: reconciling supply of and demand for science. Environmental science & policy, 10(1), 5-16.

3️⃣ The Trump Administration’s Campaign of Vengeance as Science Policy

The Trump administration’s approach to climate science policy is, by their own account, a campaign against “woke programs.” Among these “woke programs” — whatever that means — facing major funding cuts or elimination are:

- The majority of NOAA’s Office of Atmospheric Research;

- The Office of Research and Development in the Environmental Protection Agency;

- The NSF-funded National Center for Atmospheric Research;

- The multi-agency U.S. Global Change Research program;

- NASA’s earth science program.

The Trump administration’s actions appear to respond to the blueprint of Project 2025, a manifesto published by the Heritage Foundation prior to the election (and which candidate Trump claimed never to have heard of) — Here is what Project 2025 says about NOAA’s climate programs, for instance:

Together, these form a colossal operation that has become one of the main drivers of the climate change alarm industry and, as such, is harmful to future U.S. prosperity. This industry’s mission emphasis on prediction and management seems designed around the fatal conceit of planning for the unplannable. That is not to say NOAA is useless, but its current organization corrupts its useful functions. It should be broken up and downsized.

Speaking of Project 2025 in a pre-2024 election “training video,” Bethany Kozma — now a high-ranking Trump political appointee — said that the administration “will have to eradicate climate change references from absolutely everywhere” in government.

This gets us back to the two truths I espoused at the top of this post — It is at once possible to critique the Biden Administration’s approach to climate change as an “existential threat,” and recognize that there are indeed risks that should be seriously considered. That means not throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Recommended actions: The fate of federal funding and agency programs sits almost entirely with the U.S. Congress. Science organizations will lobby of course, but these battle lines have been drawn and there is not much the broader scientific community can do in the near term to affect how the vengeance campaign plays out before the mid-terms. One important step the scientific community (including climate but also much broader) is to assess how it came to be that the scientific community finds itself at “war” with the Republican party. Science is supposed to benefit all Americans, no matter who they voted for — Reestablishing our end of the social contract between science and society would be a good place for us to start, irrespective of electoral and partisan politics.

For more details on how we got here and what we might now do, see my talk in Oslo last summer, which is the second-most viewed post ever at THB:

What Did We Expect Would Happen?

2️⃣ The Invention of “Climate Risk” in Global Finance

Over the past few weeks, I’ve begun a series here at THB on the invention of “climate risk” in the global financial community. That series will continue to run into 2026. Changes in climate do indeed pose risks, but there is actually no unique risk to global financial stability that can be characterized as physical “climate risk” apart from baseline risks of extreme weather events, climate variability, and changes in climate in the broader context of changes in vulnerability and exposure.

A changing climate is a part of these risks, not a bespoke new risk that marks a break from the past.

Further, “climate risk” is, on many accounts, measured in terms of the economic costs of extreme weather events and projections from extreme and implausible climate scenarios — both of which are deeply problematic, to say the least, for measuring any kind of risk.

There is more to the story here as well (which will continue to be documented here at THB) including the creation of a cottage industry of climate risk modeling with questionable scientific quality. In addition, some of the groups being funded to provide “climate risk” scenarios for the global finance community are the same groups who create the scenarios that underlie most climate research as well as the assessment of the IPCC. There is a tangled web of institutional alignments and appearances of conflicts of interest.

Recommended actions: Much of the development of the “climate risk” industry has occurred beyond the mainstream scientific community. However, there are some important research overlaps (e.g., attribution) and questionable institutional relationships (e.g., scenarios). Leaders in the climate community, and especially those in the IPCC, shod be sure to understand the rise of “climate risk” as a parallel science-like construct outside mainstream science and assess possible risks to the integrity of climate science and its institutions.

For further reading:

The Climate-Risk Industrial Complex and the Manufactured Insurance Crisis

How the Financial System Invented “Climate Risk” Untethered from Climate Science

The Invention of “Climate Risk” – Politically Brilliant but Fatally Flawed

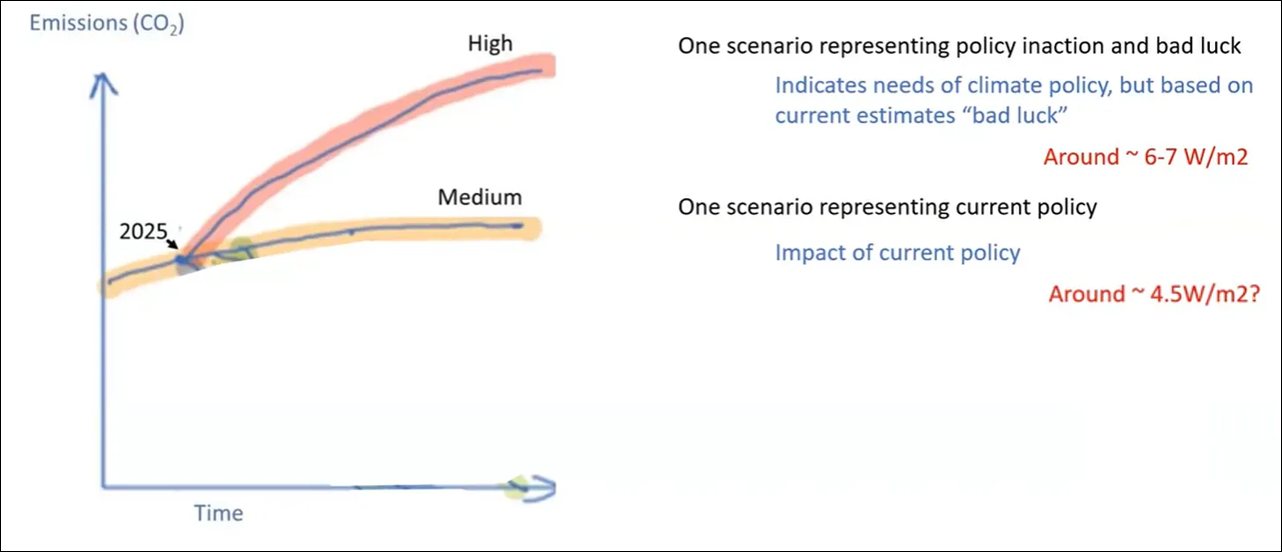

1️⃣ The Continuing Dominance of Extreme, Implausible Emissions Scenarios

Longtime readers of THB will be deeply familiar with this topic — It was the top scandal in the 2024 version of this table and stays at the top in 2025.

Long story short — Climate science and assessment have been dominated by extreme emissions scenarios for decades. Over the past five years, the community has evolved from denying that reality to overwhelmingly accepting it — that’s the good news.

The bad news is that extreme scenarios continue to dominate climate research, media reporting, and policy discussions. During 2025 alone, Google Scholar reports more than 11,000 studies that employ RCP8.5, SSP5-8.5, or SSP3-7.0. Whatever scientific merit these studies have, they have little ability to inform us reliably about future climate or its impacts.

I had expected that the next generation of climate scenarios would have been released in 2025 — They appear to be overdue. Earlier this year, based on publicly available information, I reported that the high-end scenario of the new scenarios was to be something like SSP3-7.0, another implausibly extreme scenario, as discussed at the link below.

The Apocalypse Machine Rolls On

Lately, climate advocates have begun to justify the extreme scenarios as providing evidence that climate policy is not just working, but has been incredibly successful.

Our collective view of climate science and policy has been warped by the continuing misuse of scenarios. In theory, correcting that misuse should be easy. Politically however, it would represent a fundamental reordering of the entire catastrophic climate narrative that has a tight grip on many institutions. Climate change is indeed real and a threat, but it is not the end of the world.

Recommended actions: The climate community should take steps to decentralize scenario creation, and encourage greater diversity of participation (e.g., from India, Africa and elsewhere). Physical climate research should develop a capacity to utilize scenarios that are updated on an annual basis, perhaps in parallel to the decade-long cycle currently in place. As currently structured, climate scenarios are in place to primarily meet the needs of researchers, not policy makers. That is one reason why change would be difficult. If reforms do not occur, researchers should be prepared for policy makers who decide to take matters into their own hands. Finally, and most obviously, the research community should stop its continued prioritization of implausible scenarios in research, publication, press releases, and in assessments.

Others scandals from 2025 that did not make the cut, in no particular order: