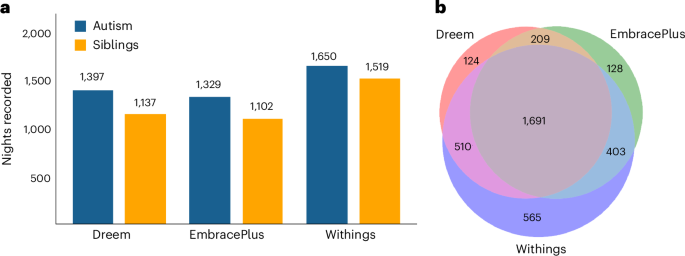

Data were successfully recorded from 102 autistic children (86 boys) and 98 nonautistic siblings (53 boys), between the ages of 10 and 17 years, from 102 families in the Simons Powering Autism Research for Knowledge (SPARK)41 cohort (Fig. 1). Children were recorded in their home setting over multiple days (EmbracePlus) and nights (all devices), with the final dataset comprising 3,630 nights: 1,691 nights recorded with all three devices, 1,122 nights recorded with two devices and 817 nights recorded with a single device (8,134 device recordings in total). Corresponding sleep diary data are also available for 2,630 of these nights. Note that the counts above refer to Dreem, EmbracePlus and Withings night-time recordings with at least 3 h of sleep (Methods).

Parents of all SSP participants completed baseline questionnaires regarding each child’s behavioral abilities and difficulties (Table 1). There were no significant correlations between the amount of data (that is, number of recorded nights) from individual autistic children per device and the children’s behavioral abilities or difficulties. This was the case for Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) total scores (r(102) > −0.17, P > 0.09), Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) total (r(102) > −0.13, P > 0.18), CBCL Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn (DSM-5)6 ADHD (r(102) > −0.07, P > 0.5), CBCL DSM-5 anxiety (r(102) > −0.16, P > 0.11) and CBCL DSM-5 depression (r(102) > −0.14, P > 0.17) scores. Similarly, there were no significant correlations with Social Responsiveness Scale, 2nd edn (SRS-2) total scores (r(102) > −0.08, P > 0.42) or Vineland Adaptive Behavior Composite (r(102) < 0.12, P > 0.23), Vineland communication (r(102) < 0.16, P > 0.1), Vineland daily living skills (r(102) < 0.1, P > 0.31) or Vineland social (r(102) < 0.14, P > 0.17) scores. There were marginally significant correlations between Repetitive Behavior Scale—Revised (RBS-R) scores and the number of nights recorded with Dreem or Empatica (r(102) < −0.21, P < 0.037, not significant after Bonferroni’s correction), but not with Withings (r(102) > −0.1, P = 0.3). Taken together, these findings show that data were collected with all three devices from children with a wide variety of behavioral abilities and difficulties in an unbiased manner.

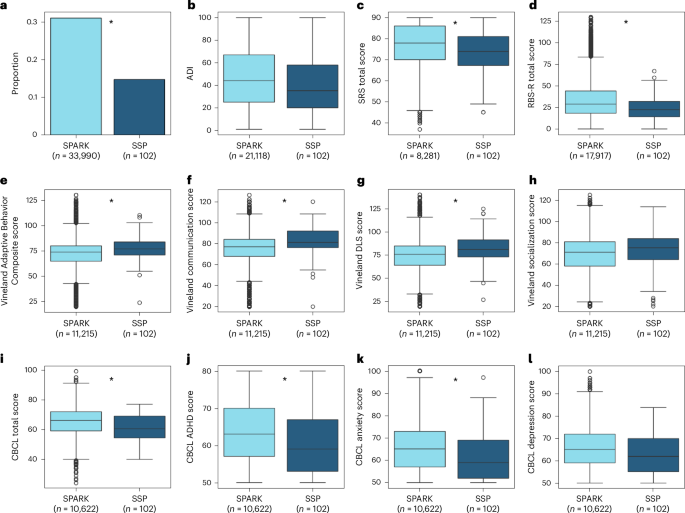

Comparison between the SSP sample and the entire SPARK cohort

Some of the questionnaires completed by parents of SSP autistic children, including the SRS, RBS-R, CBCL and Vineland, were also available for other children in SPARK, enabling us to compare our SSP sample with thousands of autistic children aged 10–17 years in the SPARK cohort (while excluding SSP children from the SPARK group). A series of Student’s t-tests revealed that SPARK children exhibited significantly higher SRS (t(103.73) = 3.45, P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.33) and RBS-R (t(103.34) = 5.76, P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.4) scores than SSP children. SPARK children also exhibited significantly higher CBCL total (t(103.26) = 5.02, P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.46), CBCL DSM-5 ADHD (t(103.20) = 4.42, P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.41) and CBCL DSM-5 Anxiety (t(103.43) = 3.94, P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.35) scores, as well as marginally significant CBCL DSM-5 Depression scores (t(103.05) = 2.82, P = 0.006, Cohen’s d = 0.27, not significant after Bonferroni’s correction). SPARK children had lower Vineland Adaptive Behavior Composite (t(103.62) = −4.39, P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −0.36), Vineland communication (t(104.42) = −5.66, P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −0.41) and Vineland daily living skills (DLS) (t(103.39) = −4.41, P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = −0.38) scores, as well as marginally significant socialization scores (t(102.89) = −2.32, P = 0.02, Cohen’s d = −0.23, not significant after Bonferroni’s correction).

Finally, the proportion of parents who reported that their children had clinically diagnosed sleep problems on the SPARK medical background questionnaire was significantly higher in SPARK than in SSP participants (χ²(1) = 12.03, P < 0.001), whereas socioeconomic status, as estimated by the 2019 national area deprivation index (ADI)42, did not differ significantly across the two groups (t(88.74) = 1.88, P = 0.06, Cohen’s d = 0.2). Hence, although the behavioral scores of SSP autistic children clearly fall within the range of SPARK children (Fig. 2), their scores, on average, indicate slightly weaker core autism symptoms, fewer behavioral and mental health challenges, fewer clinically diagnosed sleep problems and slightly better adaptive functioning.

a, Proportion of children with clinically diagnosed sleep problems as reported by parents on a medical background questionnaire (33,824 SPARK participants). b, ADI as reported in SPARK data and computed according to the participants’ address using 2019 US Census data (20,952 SPARK participants). c, SRS total scores (8,115 SPARK participants). d, RBS-R total scores (17,751 SPARK participants). e, Vineland Adaptive Behavior Composite scores (11,049 SPARK participants). f, Vineland communication scores (11,049 SPARK participants). g, Vineland DLS scores (11,049 SPARK participants). h, Vineland socialization scores (11,049 SPARK participants). i, CBCL total scores (10,456 SPARK participants). j, ADHD symptoms from the CBCL (10,456 SPARK participants). k, Anxiety symptoms from the CBCL (10,456 SPARK participants). l, Depression symptoms from the CBCL (10,456 SPARK participants). The asterisks indicate significant differences between SSP and non-SSP SPARK groups according to two-sided χ2 (a) or Student’s t-tests (all other panels), after Bonferroni’s correction for 12 comparisons (P < 0.05, corrected). The boxplots present median and interquartile range (IQR) and the whiskers are drawn to the farthest datapoint within 1.5× the IQR of the 25th or 75th percentile, respectively. Participants beyond this range are individually marked (outliers).

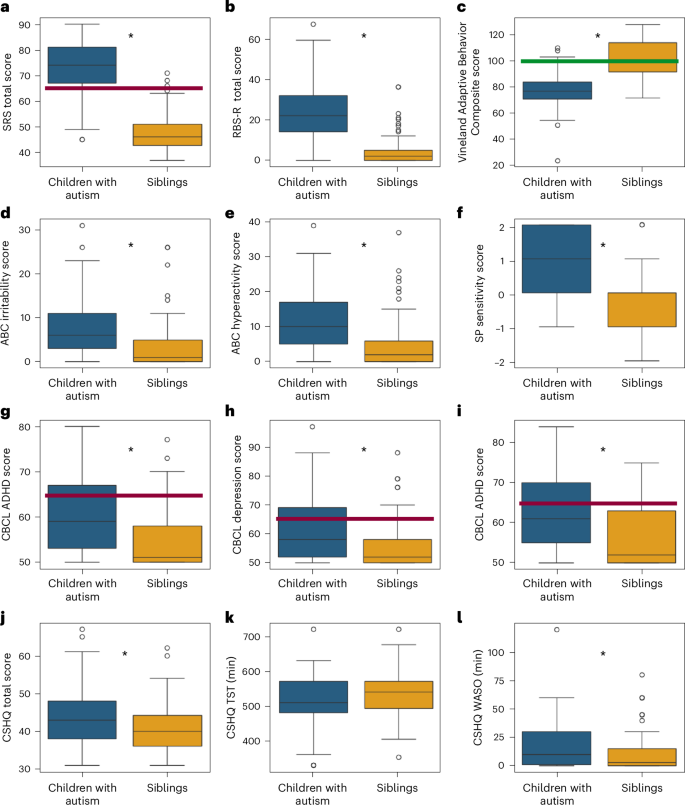

Behavioral characterization of autism and sibling groups

We examined differences across autism and sibling groups in key measures of core autism symptoms, adaptive behaviors, challenging behaviors, sensory sensitivities, co-occurring psychiatric symptoms and sleep behaviors (Fig. 3). We performed a mixed linear model analysis for each measure to assess differences across autism and sibling groups (fixed effect) while accounting for potential differences in parent reports across families (random effects), as well as the age and sex of the participating children (additional fixed effects).

a, SRS. b, RBS-R. c, Vineland Adaptive Behavior Composite. d, Irritability subscale from the ABC. e, Hyperactivity subscale from the ABC. f, Sensory sensitivity subscale from the Sensory Profile. g, ADHD symptoms from the CBCL. h, Anxiety symptoms from the CBCL. i, Depression symptoms from the CBCL. j, CSHQ total sleep disturbance score. k, CSHQ parent-reported TST in minutes. l, CSHQ parent-reported WASO in minutes. The red lines indicate the clinical cutoff (t score = 65) and the green line the population mean. The asterisks indicate significant differences between autism and sibling groups according to mixed linear model analyses (P < 0.05, two sided, uncorrected). The boxplots present median and IQR and the whiskers are drawn to the farthest datapoint within 1.5× the IQR of the 25th or 75th percentile, respectively. Participants beyond this range are individually marked (outliers).

These analyses revealed significantly higher scores in autistic children relative to their siblings on SRS total (β = 26.3, P < 0.0001, Cohen’s f2 = 2.75), RBS-R total (β = 21.1, P < 0.0001, Cohen’s f2 = 1.06), Sensory Profile sensitivity (β = 1.4, P < 0.0001, Cohen’s f2 = 0.7), ABC irritability (β = 5.3, P < 0.0001, Cohen’s f2 = 0.33), ABC hyperactivity (β = 6.5, P < 0.0001, Cohen’s f2 = 0.33), CBCL ADHD symptoms (β = 5.2, P < 0.0001, Cohen’s f2 = 0.16), CBCL anxiety symptoms (β = 6.5, P < 0.0001, Cohen’s f2 = 0.23), CBCL depression symptoms (β = 6.27, P < 0.0001, Cohen’s f2 = 0.25) and CSHQ total sleep disturbance scores (β = 3.08, P = 0.0018, Cohen’s f2 = 0.07), as well as significantly lower scores on the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Composite (β = −24.2, P < 0.0001, Cohen’s f2 = 0.88). Parent-reported TST was, on average, 16 min shorter in the autistic children relative to their siblings but did not differ significantly across groups (β = −8.42, P = 0.29, Cohen’s f2 = 0.008). Parent-reported WASO was, on average, 8 min longer in the autistic children and did differ significantly across groups (β = 7.66, P = 0.006, Cohen’s f2 = 0.05).

There was no significant effect of sex on any of the parent-reported questionnaires or measures (P > 0.1) and a significant effect of age only on ABC irritability (β = −0.05, P = 0.004), ABC hyperactivity (β = −0.04, P = 0.03) and TST (β = −0.56, P = 0.0017). Differences between siblings (within family) were considerably larger than differences across families with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) ranging between 0.16 and 0.37.

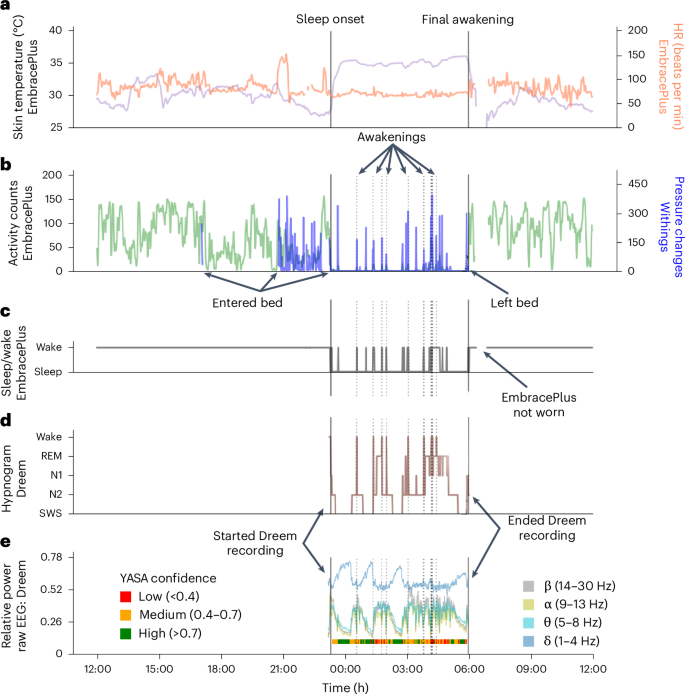

Synchronized recordings with multiple devices

EmbracePlus smartwatch data were recorded continuously when participants wore the device, Dreem3 headband data were recorded when participants activated the device before going to sleep, until they turned it off in the morning, and Withings’ mattress sensor data were recorded automatically whenever participants entered their bed. A single Samsung A51 smartphone was used to manage all devices and synchronized data acquisition to a single clock.

This design enabled us to directly compare data across multiple sensor recordings with high temporal fidelity as demonstrated in a 24-h recording from a single participant (Fig. 4). The devices yielded complementary information about the participant’s behavior and sleep or wake state during the night. For example, the activity count time course, which quantifies movements in 1-min epochs using the EmbracePlus accelerometer, was correlated with pressure changes recorded by the Withings’ sleep mat when the participant was in bed (r = 0.41, P < 0.001; Fig. 4b). Similarly, sleep and wake epochs identified by the Dreem sleep-staging algorithm in the EEG data (Fig. 4c) exhibited partial agreement with sleep and wake epochs identified by the EmbracePlus algorithm using accelerometer data (sensitivity: 0.82; specificity: 0.27; Fig. 4d). Agreement across devices and algorithms varied across participants and nights. Note that the analyses presented here used measures (that is, activity counts and sleep or wake epoch labels) that were generated by the proprietary algorithms of each device manufacturer.

a, Skin temperature (purple) and HR (orange). b, Activity counts from EmbracePlus accelerometer (green) and pressure changes from the Withings’ sleep mat (blue). c, Sleep and wake classification based on accelerometer data analyzed with EmbracePlus algorithms. d, Hypnogram from the Dreem3 automatic sleep-staging algorithm. e, Average EEG power across all Dreem EEG channels. Average δ (1–4 Hz, blue), θ (5–8 Hz, turquoise), α (9–13 Hz, yellow) and β (14–30 Hz, gray) band power demonstrate multiple sleep cycles throughout the night. The color bar below the EEG power marks segments with high (green), medium (orange) and low (red) sleep staging confidence according to the YASA algorithm, which classifies sleep stages according to EEG features in the time and frequency domains. Classification confidence is likely to depend on EEG data quality. The solid vertical lines mark sleep onset and final awakening as labeled. The dotted vertical lines mark awakenings during the sleep period according to the Dreem algorithm.

In addition, synchronized raw EEG data are also available, enabling in-depth analysis of nightly recordings with spectral analysis (Fig. 4e). To demonstrate the quality of the EEG data, we applied the Yet Another Spindle Algorithm (YASA) open-source sleep-staging algorithm43 to the raw EEG data. YASA classifies 30-s epochs of raw EEG into wake and sleep stages according to time and frequency domain EEG features. The available raw EEG data were of sufficient quality for classifying sleep stages with medium-to-high confidence in the vast majority of epochs (color bar, bottom of Fig. 4e).

Agreement across devices and with parent-reported sleep measures

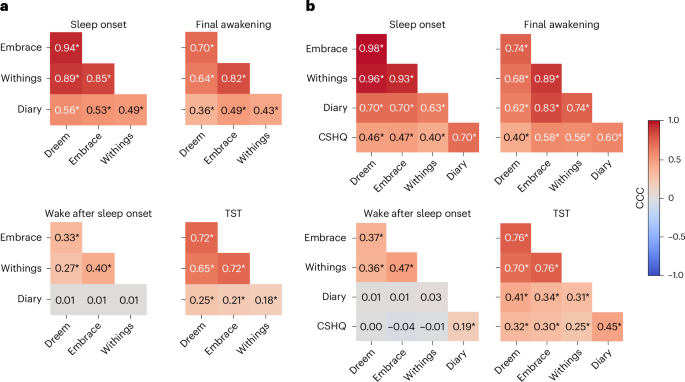

We assessed agreement across devices in identifying four basic sleep measures (Fig. 5): sleep onset (SO), final awakening (FA), WASO and TST (time from SO to FA − WASO). We identified nights where all three devices recorded the child’s sleep successfully (Methods) and then extracted SO, FA, WASO and TST as identified by the proprietary algorithm of each device per night. Note that we excluded brief awakenings that were 5 min or shorter when calculating the EmbracePlus WASO estimate to reduce its sensitivity (Methods). The same measures were also extracted from sleep diary data as reported by parents for the same nights. We limited our analyses to children with at least three nights of valid data from all devices and a sleep diary (1,153 nights from 70 autistic children and 67 siblings). This enabled us to also assess agreement between devices and diary measures that were averaged across at least three nights and parent-reported measures from questions in the CSHQ, where parents reported typical, average sleep measures per child.

a, Computed across individual nights. b, Computed across participants after averaging measures across nights (per device or diary) and adding CSHQ data. CCCs are coded by color and values are noted for each pair. The asterisks show significant correlation (*P < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected for 50 comparisons, randomization analysis).

We computed concordance correlation coefficients (CCCs) to assess agreement between pairs of devices and/or sleep diary measures across nights (Fig. 5a). This analysis demonstrated moderate-to-excellent agreement across the three devices when estimating SO, FA and TST, with weaker yet still significant CCCs for WASO. There were considerably weaker, yet still significant, CCCs between each of the devices and the sleep diary data for SO, FA and TST, but not for WASO, where there was no agreement between the sleep diary and any of the devices.

Next, we performed the same analysis after averaging each measure across all available nights per child (Fig. 5b). This yielded even stronger agreement across devices with moderate-to-excellent CCCs for SO, FA and TST, as well as weaker yet still significant CCCs for WASO. Here too there were considerably weaker, yet still significant, CCCs between each of the devices and sleep diary data for SO, FA and TST, but not for WASO. Adding the CSHQ parent-reported measures revealed moderate CCCs with each of the devices for SO, FA and TST, but not for WASO, where there was no agreement. CCCs between CSHQ and the sleep diary were significant across all measures, including WASO with poor-to-moderate values.

These analyses demonstrated an important key finding: there was far stronger agreement across sleep measures from the three independent devices than there was between any of the devices and parent-reported measures. This finding was particularly strong for WASO, where there was no agreement between devices and parents about the extent of night-time awakenings of individual children whether examining individual nights or their mean per child.

Comparison of device sleep measures across groups

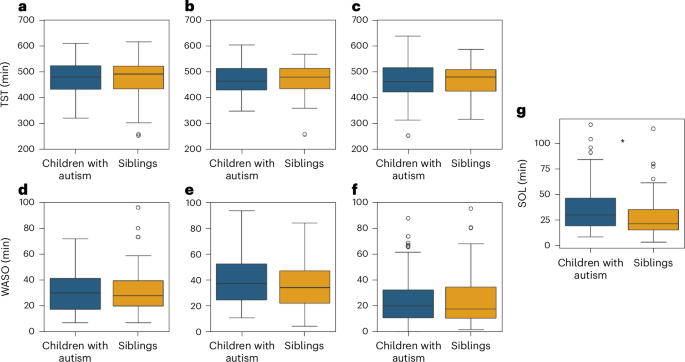

To ensure consistency, we performed all further analyses with the same subset of data described above. We did not find any significant differences between groups in objective TST or WASO measures extracted from any of the three devices (Fig. 6). TST differences between autism and sibling groups were, on average, <2.6 min according to all devices and were not significant (10.4 >β > 5.65, P > 0.16, Cohen’s f2 < 0.02). WASO differences between groups were, on average, <4.1 min according to all devices and were also not significant (β < 2.3, P > 0.53, Cohen’s f2 < 0.002). It is interesting that the ICCs of TST values from all three devices were between 0.52 and 0.62, demonstrating that much of the variance in sleep duration was explained by differences across families (that is, home environment) rather than differences in diagnosis, age or sex of the children. ICC ratios for WASO values were smaller with a range of 0.001–0.340.

a, TST from Dreem. b, TST from Embrace. c, TST from Withings. d, WASO from Dreem. e, WASO from Embrace. f, WASO from Withings. g, SOL from Dreem. The asterisks were significant differences between autism and sibling groups according to a mixed linear model analysis (P < 0.05, two sided, uncorrected). The boxplots present median and IQR and the whiskers are drawn to the farthest datapoint within 1.5× the IQR of the 25th or 75th percentile, respectively. Participants beyond this range are individually marked (outliers).

In contrast, SOL differed significantly between groups. We defined SOL as the time from Dreem recording onset to sleep onset, given that families were instructed to start the Dreem recording when the child was ready to go to sleep. We were unable to compute independent SOL measures from the EmbracePlus or Withings’ devices, because we did not have a clear indication of the time that the child was ready to go to sleep from either of these devices. Dreem-defined SOL was, on average, 7.5 min longer in autistic children relative to their siblings, a difference that was statistically significant (β = 7.37, P = 0.037, Cohen’s f2 = 0.057). There were no significant effects of sex (β = −0.03, P = 0.99) or age (β = 0.11, P = 0.13) on SOL.

Behavioral difficulties were associated with EEG-derived SOL but not WASO

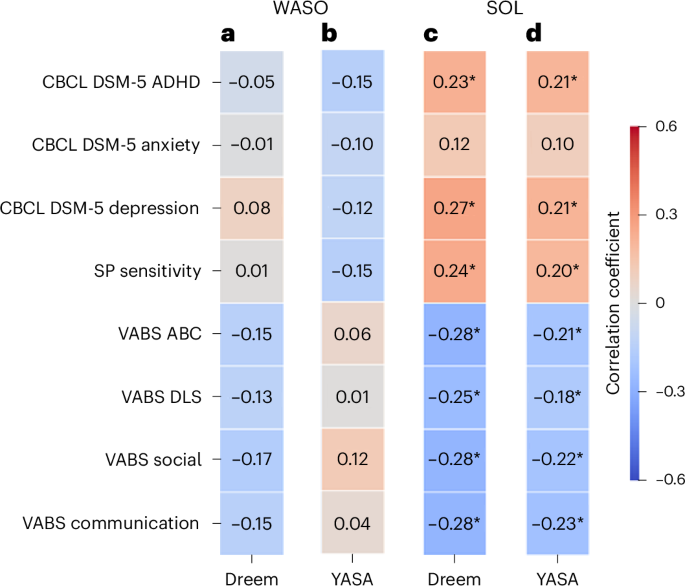

Given that EEG recordings enable direct identification of sleep and/or wake epochs and are used as the gold standard for sleep research, we focused our final analysis on EEG estimates of SOL and WASO, which measure difficulties in sleep initiation and maintenance, respectively (Fig. 7). We generated two independent estimates of each sleep measure with the Dreem and YASA43 sleep-staging algorithms, which yielded independent hypnograms per night or recording. Note that, in this analysis, we further demonstrate the utility of the raw EEG data available in the SSP, which enabled us to validate the results of the Dreem sleep-staging algorithm with the YASA algorithm43, which classifies wake and sleep stages based on EEG features in the time and frequency domains43.

a, WASO according to the Dreem algorithm. b, WASO according to the YASA algorithm. c, SOL according to the Dreem algorithm. d, SOL according to the YASA algorithm. The rows correspond to the CBCL, SP and VABS subscale scores. The asterisks indicate significant Pearson’s correlation between the sleep and behavioral measures (*P < 0.05, uncorrected).

In this analysis we adopted a dimensional approach44 and examined whether sleep disturbances were associated with behavioral difficulties across study participants, regardless of autism diagnosis. We assessed the relationship between each sleep measure and multiple parent-reported behavioral measures, including CBCL subscales for DSM-5 ADHD, anxiety and depression symptoms (three psychiatric symptom domains that are commonly associated with sleep problems), SP subscale for sensory sensitivity (also commonly associated with sleep problems) and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale (VABS) scores that are indicative of general function.

Dreem and YASA estimates of SOL were significantly correlated with all behavioral measures (|r| ≥ 0.18, P < 0.04) except for CBCL anxiety scores (r ≤ 0.12, P > 0.14). In contrast, Dreem and YASA estimates of WASO were not significantly correlated (|r| ≤ 0.17, P > 0.05) with any of the behavioral measures (Fig. 7a,b). Hence, equivalent results were apparent across independent YASA and Dreem estimates. We, therefore, averaged the SOL and/or WASO values across Dreem and YASA to create a single value of each measure per participant and computed their correlation with each of the behavioral measures noted above. We then directly compared the SOL and WASO correlation values using Steiger’s Z-tests (Methods). SOL correlations were significantly stronger than WASO correlations (P < 0.05) for all behavioral measures except CBCL anxiety and Vineland DLS scores. These results demonstrate a dissociation between EEG-defined SOL and WASO, suggesting that sleep initiation problems, rather than sleep maintenance problems, are significantly associated with a variety of behavioral difficulties and poorer adaptive behaviors, regardless of autism diagnosis.