Directed by: Tony Richardson

Written by: Tony Richardson (based on the novel by John Irving)

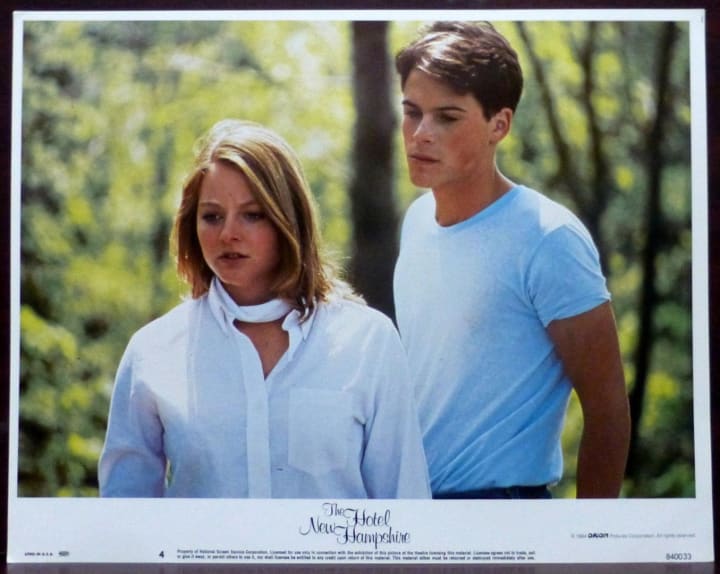

Starring: Rob Lowe, Jodie Foster, Beau Bridges, Nastassja Kinski

Release Year: 1984

There’s something almost inevitable about the idea of Wes Anderson directing a John Irving adaptation. Anderson is one of the few filmmakers who understands how absurdity and sincerity can occupy the same emotional space. His films never apologize for their weirdness. They embrace it as truth.

Most directors who’ve adapted Irving haven’t been so lucky. They’ve either flattened his eccentricity into respectable drama or misunderstood the tone entirely. Irving’s worlds are strange, yes—but they aren’t quirky in a cute or marketable way. They’re strange because life is strange. His stories are full of trauma, coincidence, grotesque humor, and emotional contradiction, all presented with a straight face.

Which makes Tony Richardson’s 1984 adaptation of The Hotel New Hampshire such a fascinating anomaly.

It may be the most faithful Irving adaptation ever made.

And that faithfulness may be exactly why it doesn’t work.

The Impossible Task of Adapting Irving

John Irving’s 1981 novel is sprawling, episodic, and deeply interior. It follows the Berry family across decades and continents, through three different hotels and a lifetime of bizarre tragedies and emotional upheaval.

There is:

• A beloved dog whose taxidermied corpse accidentally kills a grandfather

• A terrorist bombing that blinds the family patriarch

• A sibling incest storyline treated as emotional healing rather than scandal

• A woman who lives inside a bear costume

• Multiple deaths that arrive suddenly and without warning

In Irving’s hands, these events feel cohesive. His prose creates rhythm. The bizarre becomes normal because we live inside the emotional logic of the characters.

Tony Richardson’s film attempts something extraordinary: it includes almost all of it.

And that may be the central problem.

At just under two hours, the movie compresses a 500-plus page novel into a breathless series of events. Characters enter, suffer life-altering trauma, and emotionally process it within minutes. Major tragedies arrive and disappear before the audience can absorb their weight.

The film isn’t unfaithful. It’s too faithful.

The Film’s Most Famous — and Infamous — Element

It’s impossible to discuss The Hotel New Hampshire without acknowledging the element that has largely erased it from popular memory.

Rob Lowe and Jodie Foster play siblings, John and Franny Berry. Franny and John end up having sex in a comical presentation, sped up film, sped up time. The film presents this not as scandalous, but as healing—a way for both of them to reclaim emotional control and move forward. And, no, it’s not funny or cute or ‘healing.’ It’s jarring, uncomfortable and needless. It exists because it is in the book and plays like a way to shock audiences more than anything.

The film doesn’t present this quietly. It presents it through a montage scored like a celebratory release. It is surreal, uncomfortable, and emotionally disorienting.

This isn’t something invented by the movie. It’s in Irving’s novel.

But Irving’s prose contextualizes it. The film can only present it.

Without the internal emotional scaffolding of the book, the moment feels less like psychological complexity and more like narrative shock.

It’s one of many moments where fidelity becomes distortion.

Capturing Irving’s Spirit — and Losing It

To Richardson’s credit, the film captures Irving’s worldview more faithfully than most adaptations. The Berry family endures unspeakable loss but refuses despair. Their philosophy is simple:

Keep passing the open windows.

Life is chaos. Survival itself is victory.

The film retains Irving’s dark humor, his fairy-tale symbolism, and his belief that families are defined by endurance rather than stability. Nastassja Kinski’s Susie, a woman who hides inside a bear costume out of emotional insecurity, embodies Irving’s central metaphor: protection is often artificial, but no less necessary.

Where the film struggles is in emotional continuity.

Irving’s novel moves with dream logic. Richardson’s film moves with narrative urgency. Events pile up so quickly that characters sometimes feel less like people and more like participants in a series of bizarre incidents.

What feels profound in the novel can feel arbitrary on screen.

John Irving’s Own Verdict

Interestingly, John Irving himself viewed the film positively.

He admired Richardson’s willingness to embrace the story’s bizarre tone rather than sanitize it. He appreciated the film’s use of Jacques Offenbach’s music, which he described as transforming the story into a kind of “sexual cancan,” emphasizing its chaotic, absurd rhythm.

Irving’s primary criticism wasn’t that the film misunderstood his work.

It was that Richardson tried to include too much.

By attempting to preserve the novel in its entirety, the film sacrificed the emotional depth that made the story resonate.

In other words, the adaptation’s greatest strength was also its fatal flaw.

A Faithful Adaptation That Feels Like a Dream

The Hotel New Hampshire isn’t a bad movie.

It’s a strange movie. A fascinating movie. A movie that feels slightly out of sync with itself.

It captures the events of Irving’s novel but struggles to capture its emotional rhythm. Watching it feels less like experiencing a traditional narrative and more like remembering a dream—disconnected, unsettling, and occasionally profound.

Perhaps that’s appropriate.

Irving’s stories were never meant to feel normal.

They were meant to feel true.