Scientists have many theories about how Earth’s raw materials turned into living cells, but a new proposal is particularly slimy.

In a recent paper, an international team argues that life may have first emerged within a blob of sticky goo clinging to a rock, long before true cells existed.

Similar to the bacterial biofilms we see today on rocks, pond surfaces, and even your unbrushed teeth, a semi-solid gel matrix would provide the perfect place for life to set up shop, the authors propose, both on Earth and, potentially, on other planets.

This jelly-life notion is a bit niche: Most origin-of-life theories set the scene for the first organic chemistry in water, not goo.

But those theories also struggle to explain how simple molecules of the kind that were probably floating around in Earth’s waters could have transformed into something as complex as RNA (ribonucleic acid) or DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) without some extra support.

A gel-like environment could solve several of those issues at once.

“While many theories focus on the function of biomolecules and biopolymers, our theory instead incorporates the role of gels at the origins of life,” says Hiroshima University astrobiologist Tony Jia.

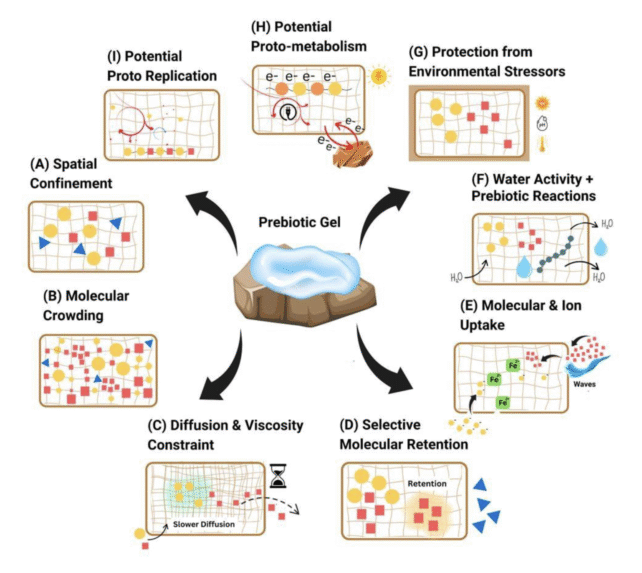

A gel medium, Jia and co-authors propose, would be able to trap and organize molecules into formations stable enough to overcome some key barriers in pre-life chemistry.

Early Earth was not the relatively mild, ozone-blanketed place we know today. Intense ultraviolet radiation could hit the surface unimpeded, and temperatures were extreme.

Prebiotic gels, the team suggests, could have offered much-needed protection to life’s fragile chemistry, long before actual membrane-bound cells had a chance to develop.

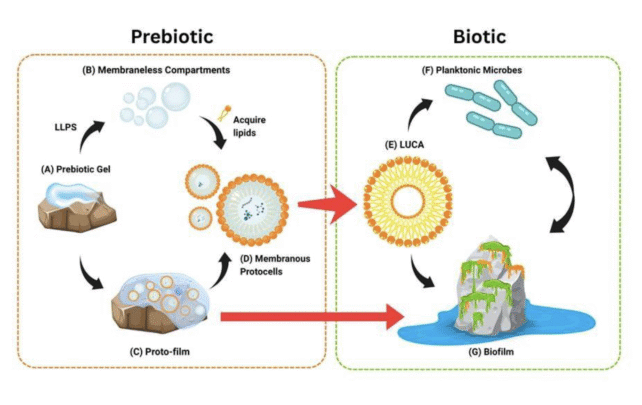

In this theory, which was first proposed in 2005 and expanded on here, protocells were not the first step in the origin of life, but rather the outcome of the chemical organization established by the primordial goo.

“Here, we outline the prebiotic gel-first framework, which considers that early life may have emerged within surface-attached gel matrices,” the researchers write.

“Such prebiotic gels may have allowed primitive chemical systems to overcome key barriers in prebiotic chemistry by enabling molecular concentration, selective retention, reaction efficiency, and environmental buffering.”

In these early gels, they propose, the first murmurs of a metabolism could have arisen as chemicals traded electrons. Along with visible and infrared light, ultraviolet light penetrating the gel could have provided additional energy for chemical reactions within, much as photosynthesis does in plants today.

Related: Mars Organics Are Hard to Explain Without Life, NASA-Led Study Finds

Gels can concentrate monomers, such as activated nucleotides and amino acids, the team adds, and are composed in a way that selectively retains and interacts with certain chemicals, not others.

The moist but not-quite-wet environment within a gel matrix favors reactions that can link monomers together to form polymers – complex molecules like those in our own bodies – as opposed to hydrolysis reactions, in which chemicals break down into smaller parts.

This broadens what we’re looking for when it comes to life beyond Earth, too. Structures like gels, rather than specific chemicals, may be targets in future missions looking for life in space.

The research was published in ChemSystemsChem.