Long before the orchestras and choirs of modern coronations, music played a central role in crowning England’s kings. What might have been sung at the coronation of Edward the Confessor in 1043?

By Sonja Maurer-Dass

Music and England’s royal coronations are inextricable. Since the mid-eighteenth century, the coronations of the nation’s monarchs have been elevated by the works of prominent composers, most notably the opulent coronation anthem, “Zadok the Priest.” This piece, with its regal instrumentation that consists of orchestra—including timpani and brass—and choir, was one of four anthems written by the prolific and celebrated eighteenth-century composer George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) for King George II’s coronation on October 11, 1727.

The music played at England’s coronations has been well documented for the past three centuries; however, coronation music of many centuries prior, particularly of the Middle Ages, is more elusive due to fewer extant written accounts. Nonetheless, the information that does survive provides us with some insight into the music that accompanied kings and queens as they proceeded to the throne.

One king, some of whose coronation music was documented, is Edward the Confessor (1003/05–1066), whose coronation ceremony is thought to have been honoured by music from one of England’s most important medieval music manuscripts, the Winchester Troper. In the following sections, we will survey the events that led to Edward the Confessor’s coronation, his coronation procession and ceremony, and the music that accompanied both.

The Road to Kingship

Edward the Confessor was born at Islip in Oxfordshire in c. 1003–1005 to Æthelred the Unready (966–1016) of the House of Wessex and Emma of Normandy (984–1052). Today, he is remembered for his piety and his rule as one of England’s last Anglo-Saxon kings. Like many rulers, Edward’s road to kingship was riddled with uncertainty and tumult. In 1013, when he was a child, the Danes—led by King Sweyn Forkbeard (963–1014)—occupied England, which forced Edward and his family to flee to his mother’s homeland, Normandy. Upon Sweyn’s death the following year, negotiations were made that restored Æthelred to power and consequently allowed Edward and his family to return to England.

However, the security that this restoration of power provided was short-lived, as Edward’s father died only a few years later in 1016. Again, the Danes seized England’s throne—this time by Cnut the Great (†1035), the son of Sweyn Forkbeard—which forced Edward into many years of exile in Normandy. It wasn’t until 1042, after years of political turmoil and England’s crown passing between multiple hands, that Edward finally ascended to power in his homeland.

According to the Vita Ædwardi Regis (c. 1075), a work written by an anonymous author that recounts the life of Edward the Confessor, his return and reclamation of England was a time of celebration and a sign of God’s blessings on the land. According to Edward’s Vita: “Everywhere Edward was acclaimed with loyal undertakings of submission and obedience.”

The King’s Coronation: Ceremony and Music

On Easter Day, April 3, 1043, Edward the Confessor was crowned king of England at Winchester Cathedral by Archbishops Eadsige of Canterbury and Ælfric Puttoc of York. The decision to hold the royal coronation on Easter Sunday was made, no doubt, to enhance the religiosity surrounding Edward’s role as king. As for the coronation ceremony, it was based upon the Second English Coronation Ordo, one of the oldest sources that outlined the rite of anointing kings in Anglo-Saxon England.

According to historian Frank Barlow, the coronation ceremony began with a stately procession. Edward was accompanied by two bishops, who led him (by hand) to Winchester Cathedral. The solemnity of the procession was further ennobled by choristers who sang: “Let thy hand be strengthened, and thy right hand be exalted. Let justice and judgement be the preparation of thy seat and mercy and truth go before thy face.”

Barlow explains that once Edward and his bishops arrived at the cathedral, they lay prostrate in front of the high altar. Next, the bishops turned to the rest of the clergy and the country’s people who were in attendance and asked if Edward would be embraced as their new king. This was followed by singing the hymn Te deum laudamus. After taking his oaths (which Barlow suggests could have been recited in the vernacular) and a series of prayers related to kingship and Christianity, Edward experienced the most significant ritual of a royal coronation—anointing. During this ritual, the king’s head was rubbed with holy oil—a tradition with biblical roots that imitates the anointing of ancient Hebrew kings and high priests such as King David and Aaron—and was accompanied by the singing of the song Unxerunt Salomonem (“They Anointed Solomon”, referring to the anointing of the biblical King Solomon by Zadok the Priest).

Following his anointment, Edward was fitted with royal regalia, which included a ring, sword, crown, sceptre, and rod (Barlow states that these items were given to kings in that specific sequence), and was then blessed by the archbishop:

May God make you victorious and a conqueror over your enemies, both visible and invisible; may he grant you peace in your days and with the palm of victory lead you to his eternal Kingdom… May he grant that you be happy in the present world and share the eternal joys of the world to come. May God bless this our chosen king that he may rule like David… govern with the mildness of Solomon and enjoy a peaceable kingdom.

This was followed by singing: “Vivat rex! Vivat rex! Vivat rex in eternum!” The final component of the coronation ceremony was a mass that was celebrated in honour of the newly crowned king.

In the account of Edward’s coronation and procession, the singing of several hymns is mentioned; however, the sacred music of the coronation mass is less clear. Despite this uncertainty, some scholars posit that the music sung during the ceremony can be identified in the Winchester Troper.

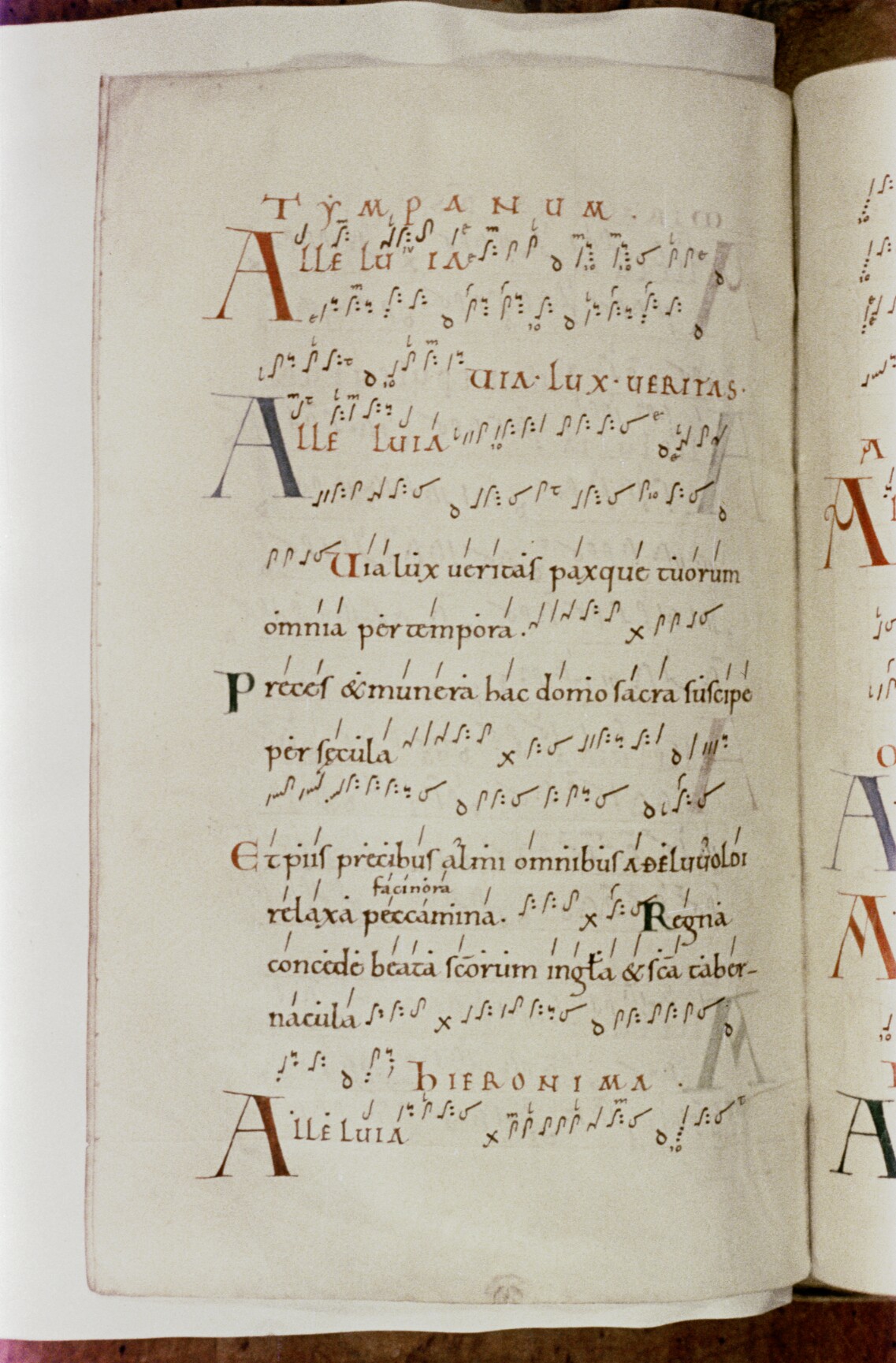

Music of the Winchester Troper

Dating back to the mid-eleventh century, the Winchester Troper is one of the largest compilations of two-part polyphonic music that was organised for the liturgy (polyphonic music is that which contains multiple, independent melodic lines that are sung—or played—simultaneously). As evinced by its name, the troper was associated with Winchester Cathedral. A troper is a collection of “tropes,” which musicologist Margot Fassler defines as: “an addition of a sung phrase of music to comment upon a pre-existing chant.” For context, “chant” refers to a type of sacred, unaccompanied singing, such as Gregorian chant or plainchant.

Consisting of two manuscripts, the Winchester Troper was initially created in the 1020s by one person who was likely the Winchester Cathedral cantor. It is the music that was later added in the 1030s–1040s that is believed to have been used at Edward the Confessor’s coronation, quite possibly the music composed for Easter.

Unfortunately, we cannot be certain of all the music that was part of Edward the Confessor’s coronation (or many other medieval coronations); yet, what is quite certain is that music would have played an integral role in glorifying the reign of England’s new monarch, much as it has in more recent centuries past up to the coronation of England’s newest king, Charles III.

Dr. Sonja Maurer-Dass is a Canadian musicologist and harpsichordist. She holds a PhD in Musicology from The University of Western Ontario (London, Ontario, Canada) and a master’s degree in Musicology specializing in late medieval English music from York University (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Sonja has taught Baroque music history at McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario, Canada) and undergraduate tutorials on different topics in musicology and music theory at The University of Western Ontario. Her work has been published in the Medieval Magazine, Ancient History Magazine, Ceræ: An Australasian Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, and Medievalists.net

Click here to read more from Sonja Maurer-Dass

Further Readings:

Barlow, Frank. Edward the Confessor. Yale University Press, 1997.

Everist, Mark, editor. The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Music. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Fassler, Margot. Music in the Medieval West: Western Music in Context. W.W. Norton and Company, 2014.

Top Image: Edward being crowned in this thirteenth-century Life of Edward the Confessor- Cambridge University Library MS Ee.3.59. fol. 9r.