Supernovae are the spectacular explosions that result from dying massive stars, seeding the universe with heavy elements like carbon and iron. Kilonovae occur when two binary neutron stars begin circling into their death spiral, sending out powerful gravitational waves and stripping neutron-rich matter from each other. Then the stars collide and merge, producing a hot cloud of debris that glows with light of multiple wavelengths. It’s the neutron-rich debris that astronomers believe creates a kilonova’s visible and infrared light—the glow is brighter in the infrared than in the visible spectrum, a distinctive signature that results from heavy elements in the ejecta that block visible light but let the infrared through.

This latest kilonova candidate event, dubbed AT2025ulz, initially looked like the 2017 event, but over time, its properties started resembling a supernova, making it less interesting to many astronomers. But it wasn’t a classic supernova either. So some astronomers kept tracking the event and analyzing combined “multimessenger” data from other collaborations and telescopes during the same time frame. They concluded that this was a multi-stage event: specifically, a supernova gave birth to twin baby neutron stars, which then merged to produce a kilonova. That said, the evidence isn’t quite strong enough to claim this is what definitely happened; astronomers need to find more such superkilnova to confirm.

DOI: Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2025. 10.3847/2041-8213/ae2000 (About DOIs).

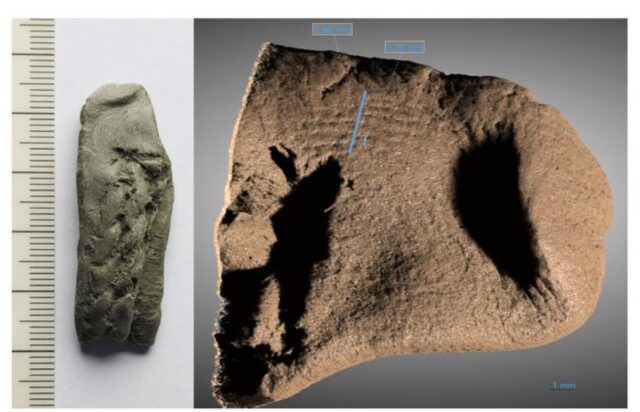

An ancient seafarer’s fingerprint

Credit:

Photography by Erik Johansson, 3D model by Sahel Ganji

In the 4th century BCE, an invading mini-armada of about four boats attacked an island off the coast of Denmark. The attack failed and the victorious islanders celebrated by sinking one of the boats, filled with their foes’ weapons, into a bog, where it remained until it was discovered by archaeologists in the 1880s. It’s known as the Hjortspring boat, and archaeologists were recently surprised when their analysis uncovered an intact human fingerprint in the tars used to waterproof the vessel. They described their find in a paper published in the journal PLoS ONE.