Modern game development has proven to be a tricky beast, especially when differing creative purposes have resulted in lots of varying results. While some games purport to be entire worlds and succeed in that intention, others get caught up in countless side missions, fetch quests, and forgettable mini-games. Especially in the realm of blockbuster development and AAA release, the cross-section of ambition and intention can be a surprisingly tricky needle to thread. It’s partly why so many major game releases now feel overstuffed, with “feature creep” seeing technically impressive games suffer from too many fine but forgettable elements in a bid to deliver the most broadly appealing game possible.

That’s partly what makes the development of Fallout 3 stand out so much in retrospect. The classic FPS/RPG was an impressive technical release when it launched, but one that didn’t let its central gameplay and narrative get overtaken by too many elements. The development team at Bethesda set out to create an open world but knew when to hold back or cut an idea if it became too distracting. One of the key creatives on that title recently reflected on the development cycle of the title and a major principle the team followed during production — and how it specifically helped them avoid feature creep. It’s the sort of gaming development fundamental that more modern game makers should keep in mind, especially when working on more ambitious games that can easily go from immersive to overstuffed.

Fallout 3 Benefited From Feature Seep, Not Content Creep

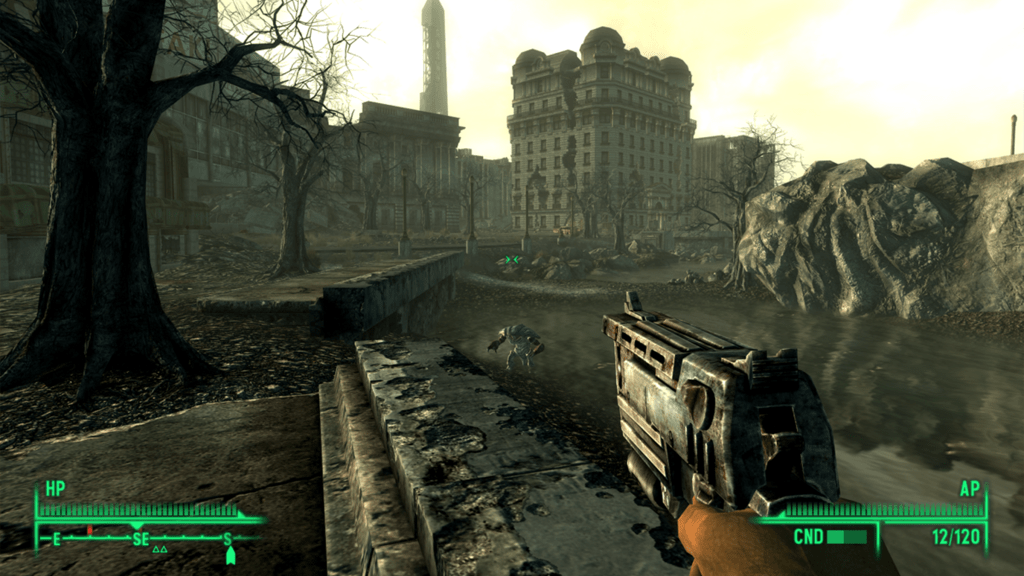

Fallout 3 is one of the biggest releases that Bethesda has ever had, with the 2008 title serving as their first tackle of the material after acquiring the rights to the series. The open-ended and morally flexible adventure benefited from strong storytelling and tight game design. While it was a game with incredible depth, none of it was unnecessary in terms of narrative or gameplay. It turns out that was very much by design and something that the team at Bethesda Game Studios was keenly aware of.

During an interview with Game Informer, Fallout 3 designer and writer Emil Pagliarulo noted that one of the key discoveries the team made during development was the decision to start cutting content if they felt the game didn’t have the ability to fully realize the idea. Specifically, Pagliarulo recalled how “I remember at one point, our lead animator at the time, Hugh Riley, he made a comment in a meeting that said, ‘We have the opposite of feature creep. We have feature seep,’ meaning that we were cutting things… We were really smart about cutting things, because we knew that we couldn’t do it. We were tackling the scale. And so, during development, we felt really good.”

The idea of “feature seep” is an especially interesting way to look at game design, especially in a modern context where cutting-edge tech can be used to create truly massive games. By recognizing the elements of the game that would have been too taxing, distracting, or ambitious for the game they were making, the developers took cool but potentially unwieldy concepts (such as the ability to join other factions) out of the game. This instead allowed them to focus more heavily on the elements they wanted to nail and use all the additional elements of the game to reinforce those aspects. It’s a great way to approach game design, and something that a lot of modern developers could learn a lot from.

Not Every Game Has To Be Everything

As games have gotten more capable of creating entire worlds, developers have sometimes made the mistake of thinking they need to fully fill them. This can result in a deluge of features and gameplay modes that aren’t complementary to the primary gameplay loop, with maps full of minor missions that just pad out the run-time without feeling fun enough to be genuine standouts themselves. These elements can clutter a game experience and distract from what makes it so engaging in the first place.

The result is game bloat and feature creep, which can severely impact an ideal game design. Especially in modern game design, it seems that many of the best games tend to be the ones that focus on a central game dynamic and build out the world from there. While some games can justify that massive scope, others falter under the weight of too many bells and whistles.

Too many features for the sheer sake of it can sometimes distract from what makes a game work on a fundamental level. If the feature doesn’t improve the central game, it needs to be cut. That’s what Fallout 3 did, and it paid amazing dividends not just for that game but also for the ones that followed it in the series. That approach helped keep the team on point and delivered on the concept that animated the team in the first place. It’s a principled approach that the best games of this era have refined and that other developers should try to match.