The alarming claim that we make 200 daily food decisions isn’t exposing hidden habits, it’s exposing a misleading number.

Numbers often drive health advice. They are meant to inform, motivate, and guide behavior. But not every widely shared statistic rests on solid scientific ground. One long repeated claim says people make more than 200 food-related decisions every day without realizing it.

According to Maria Almudena Claassen, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Adaptive Rationality at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, that figure gives a misleading impression. “This number paints a distorted picture of how people make decisions about their food intake and how much control they have over it,” she says.

Claassen, along with Ralph Hertwig, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, and Jutta Mata, an associate research scientist at the Institute and Professor for Health Psychology at the University of Mannheim, published research examining how this number became so influential. Their work shows how questionable measurement methods can shape public understanding of eating behavior in inaccurate ways.

The Origin of the 200 Food Decisions Claim

The widely cited estimate dates back to a 2007 study by U.S. scientists Brian Wansink1 and Jeffery Sobal. In that study, 154 participants were first asked to estimate how many decisions they made each day about eating and drinking. The average response was 14.4 decisions.

Participants were then asked to break down their choices for a typical meal into categories such as “when,” “what,” “how much,” “where,” and “with whom.” Researchers multiplied these estimates by the number of meals, snacks, and beverages participants said they consumed in a typical day. When combined, this calculation produced an average of 226.7 daily decisions.

The difference between the initial estimate and the larger total, 212.3 decisions, was interpreted as evidence that most food choices are unconscious or “mindless.”

Why Researchers Question the Number

Claassen and her colleagues argue that this conclusion is flawed. They point to both methodological and conceptual weaknesses in the original design and say the discrepancy can be explained by a well known cognitive bias called the subadditivity effect.

The subadditivity effect describes a tendency for people to give higher numerical estimates when a broad question is divided into several specific parts. When food decisions are counted piece by piece, totals naturally rise. According to the researchers, the large number of supposed “mindless” choices reflects this cognitive pattern rather than an observed reality about how people eat.

They also warn that repeating simplified claims can shape public perception in harmful ways. “Such a perception can undermine feelings of self-efficacy,” says Claassen. “Simplified messages like this distract from the fact that people are perfectly capable of making conscious and informed food decisions.”

Defining Food Decisions in Real Life

The research team argues that food choices should be examined in context rather than reduced to a single headline number. Meaningful questions include what is being eaten, how much is consumed, what is avoided, when the choice occurs, and the social or emotional setting surrounding it.

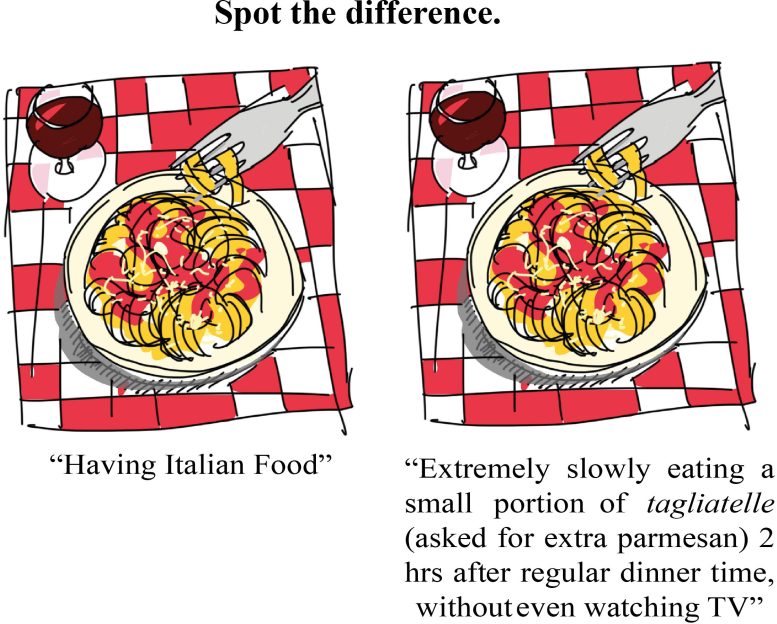

Food decisions happen in specific situations, such as choosing between salad and pasta or deciding whether to skip a second helping. The most important choices are those that connect to personal goals. For someone trying to lose weight, that may mean selecting a lighter option at dinner. For someone focused on sustainability, it may involve choosing a vegetarian meal over a meat-based one.

Why Multiple Research Methods Matter

To better understand everyday eating behavior, the researchers advocate methodological pluralism. This approach combines qualitative observation, digital tracking tools, diary studies, and cross cultural research to create a more accurate and nuanced picture of how food decisions are made.

Ralph Hertwig emphasizes that attention-grabbing statistics can distract from deeper insights. “Magic numbers such as the alleged 200 food decisions do not tell us much about the psychology of eating decisions, even more so if these numbers turn out to be themselves distorted,” he says.

“To get a better understanding of eating behavior, we need to get a better grasp of how exactly decisions are made and what influences them.”

How Self-Nudging Supports Healthy Choices

Understanding how food decisions work can help people build healthier habits. One practical strategy highlighted by the researchers is self-nudging. This means arranging your surroundings so that healthier options are easier to choose.

For example, placing pre-cut fruit at eye level in the refrigerator or storing sweets out of sight can support long-term goals without requiring constant willpower. Self-nudging is part of the boosting approach, which focuses on strengthening personal decision-making skills rather than depending on external cues (Reijula & Hertwig, 2022).

In Brief

- The claim that people make more than 200 unconscious food decisions per day has circulated widely, but it stems from a methodologically problematic study and creates a distorted view of decision-making.

- Oversimplified statistics can weaken self-efficacy and falsely suggest that eating behavior is largely beyond conscious control.

- Researchers at the MPI call for methodological pluralism when studying food decisions.

- Practical strategies such as self-nudging can support informed, health-promoting choices.

Notes

- While Brian Wansink was removed from his academic position and had 18 of his articles retracted, the study discussed here has not been retracted. Our critique focuses not on misconduct but on methodological and conceptual shortcomings inherent in the study’s design.

References:

“The (mis-)measurement of food decisions” by Maria Almudena Claassen, Jutta Mata and Ralph Hertwig, 25 February 2025, Appetite.

DOI: 10.1016/j.appet.2025.107928

“Self-nudging and the citizen choice architect” by SAMULI REIJULA and RALPH HERTWIG, 26 March 2020, Behavioural Public Policy.

DOI: 10.1017/bpp.2020.5

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.